Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

It appears as though the market for satellite radio may not be big enough for two firms to profitably survive, although one merged "monopoly" firm might survive. But the antitrust government authorities appear to seriously be considering to forbid the merger.

If they do so, they will be presuming to tell the consumer that she is better off with no satellite radio, than with one merged "monopoly" satellite radio.

Note the secondary issue of whether it’s appropriate to call a merged company a "monopoly." If the "industry" is defined as "satellite radio," then the merged company would be a monopoly. If the "industry" is more broadly defined as "broadcast radio," which would include AM, FM, and internet stations, then the merged firm would be a long way from a monopoly.

But either way, the government should stay out of it.

(NYT, A1) The nation’s two satellite radio services, Sirius and XM, announced plans yesterday to merge, a move that would end their costly competition for radio personalities and subscribers but that is also sure to raise antitrust issues.

The two companies, which report close to 14 million subscribers, hoped to revolutionize the radio industry with a bevy of niche channels offering everything from fishing tips to salsa music, and media personalities like Howard Stern and Oprah Winfrey, with few commercials. But neither has yet turned an annual profit and both have had billions in losses.

. . .

Questioned last month about a possible Sirius-XM merger, the F.C.C. chairman, Kevin J. Martin, initially appeared to be skeptical, but later said that if such a deal were proposed, the agency would consider it.

In a statement yesterday, Mr. Martin acknowledged that the F.C.C. rule could complicate a merger but said the commission would evaluate the proposal. “The hurdle here, however, would be high,” he said.

The proposed merger, first report-(p. C2)ed yesterday by The New York Post, promises to be a test of whether regulators will see a combination of XM and Sirius as a monopoly of satellite radio communications or whether they will consider other audio entertainment, like iPods, Internet radio and HD radio, to be competitors.

“If the only competition to XM is Sirius, then you don’t let the deal through,” said Blair Levin, managing director of Stifel Nicolaus & Company and a former F.C.C. chief of staff. But Mr. Blair said he expected the F.C.C. to approve the merger.

For the full NYT story, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(WSJ, p. A1) But because XM and Sirius are the only two companies licensed by the Federal Communications Commission to offer satellite radio in the (p. A13) U.S., the deal is likely to face significant regulatory obstacles.

Broadcasters said yesterday that they will fight the proposed merger, and FCC Chairman Kevin Martin released an unusually grim statement saying that the two companies will face a "high" hurdle, since the FCC still has a 1997 rule on its books specifically forbidding such a deal which would need to be tossed. The transaction also requires the Justice Department’s blessing.

Indeed, XM and Sirius may be rushing into a deal because they sense the regulatory terrain will only get tougher. People close to the matter said that the two companies acted because the climate is already changing with the election of a Democratic-controlled Congress. Future developments — such as the possibility of a Democratic president — could make it even harder for the proposed merger to pass muster.

In their strategy, the two companies may be subtly acknowledging the risks before them: By conceiving their deal as a merger of equals and declining to say which company name would emerge ascendant, they minimize the business risks should the deal fall through. If, for example, the combined company were to be dubbed Sirius, XM could be vulnerable to a decline in sales during a regulatory review period that could last a year. A person familiar with the negotiations said the two companies have set March 1, 2008, as their "drop-dead date," after which either side can walk away if approval is not granted.

The coming regulatory battle is likely to focus on the definition of satellite radio’s market. The two companies are expected to argue that the rules established a decade ago, which require two satellite rivals to ensure competition, simply don’t apply in today’s entertainment landscape.

Since 1997, a host of new listening options have emerged, making the issue of choice in satellite radio less important for consumers. Executives cite a new digital technology called HD radio, iPod digital music players, Internet radio and music over mobile phones as competitors that didn’t exist when the satellite licenses were first awarded.

For the full WSJ story, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

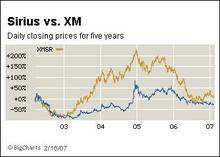

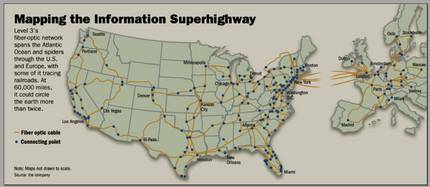

Source of graphic on left: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of graphic on right: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graphic on left: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of graphic on right: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

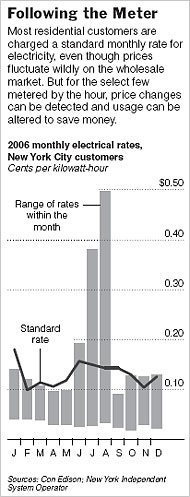

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Level 3 stock prices. Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Level 3 stock prices. Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below. CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.

CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below. Source of book image:

Source of book image:

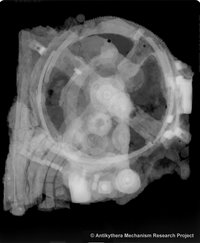

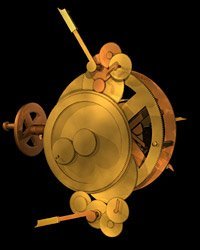

A computer model re-construction of the Antikythera Mechanism. Source of image:

A computer model re-construction of the Antikythera Mechanism. Source of image: