Source of book image: http://t0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQPLdrVlC1FT3ojxyxWJLq55AeAs87pw_Bw6ks1ugFnkcI_DBa_1w&t=1

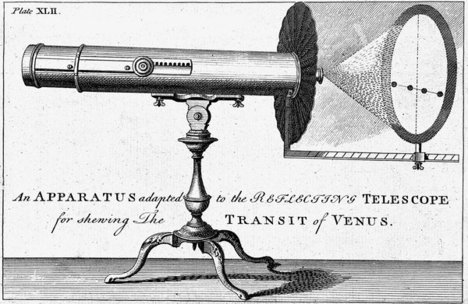

(p. 23) Next time you find yourself grousing when the passenger in front reclines his seat a smidge too far, consider the astronomers of the Enlightenment. In 1761 and 1769, dozens and dozens of stargazers traveled thousands of miserable miles to observe a rare and awesome celestial phenomenon. They went by sailing ship and open dinghy, by carriage, by sledge and on foot. They endured discomfort that in our own flabby century would generate years of litigation. And they did it all for science: the men in powdered wigs and knee britches were determined to measure the transit of Venus.

. . .

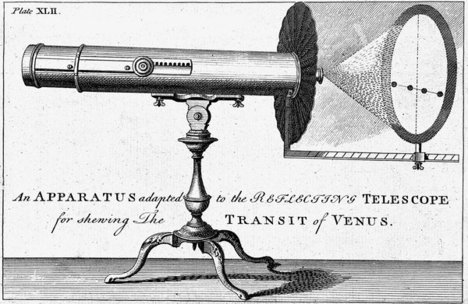

The British astronomer Edmond Halley had realized that precise measurement of a transit might give astronomers armed with a clock and a telescope the data they needed to calculate how far Earth is from the Sun. With that distance in hand, they could work out the actual size of the solar system, the great astronomical problem of the era. The catch was that it would take multiple measurements from carefully chosen locations all over the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. But that was somebody else’s problem. Halley knew he wouldn’t live to see the transit of 1761.

That challenge fell to the French astronomer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, who managed to energize and rally his colleagues in the years leading up to the transit, then coordinate the enormous effort that would ultimately involve scientists and adventurers from France, Britain, Russia, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Sweden and the American colonies. When you think about how hard it is to arrange a simple dinner with a few friends who live in the same city and use the same language when e-mailing, it’s enough to take your breath away.

. . .

Sea travel was so risky in 1761 that observers took separate ships to the same destination to increase the chances some of them would make it alive. The Seven Years’ War was on, and getting caught in the cross-fire was a constant concern. One French scientist carried a passport arranged by the Royal Society in London advising the British military “not to molest his person or Effects upon any account.” Others were shelled by the French or caught in border troubles with the Russians. An observer en route to Tobolsk, in Siberia, found himself floating in ice up to his waist when his carriage fell through the frozen river they were traveling in lieu of a road. He made it to his destination. Another, heading toward eastern Finland via the iced-over Gulf of Bothnia, was repeatedly catapulted out of his sledge as the runners caught on the crests of frozen waves. He made it too.

For the full review, see:

JoANN C. GUTIN. “Masters of the Universe.” The New York Times Book Review (Sun., May 20, 2012): 19.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date May 18, 2012.)

The full reference for the book under review, is:

Wulf, Andrea. Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

Source of image: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of image: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.