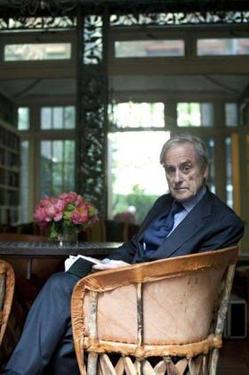

“Evans says: “Ultimately, Mrs Thatcher was the reason I was fired, because I attacked her so much.” Source of caption and photo: online version of The Independent on Sunday article quoted and cited below.

(p. 12) As a condition of acquiring both The Times and The Sunday Times in early 1981, Murdoch promised that the independence of each would be protected by a board of directors, and made other solemn guarantees.

“On this basis,” Evans wrote in Good Times, Bad Times, “I accepted Rupert Murdoch’s invitation to edit The Times on February 17 1981. My ambition,” he admitted, “got the better of my judgement.” Every assurance regarding editorial independence, he added, was blithely disregarded.

On 9 March 1982, the day after he’d come back from burying his father at Bluebell Wood cemetery in Prestatyn, Harold Evans was sacked.

“Ultimately,” he says, “Mrs Thatcher was the reason I was fired. Because I was attacking her so much. When she started to dismantle the British economy, the most cogent critic of that policy which led, OK, to… a lot of things… was The Sunday Times. I wrote 70 per cent of that criticism myself. When I became editor of The Times, I continued to criticise monetarism. But I could still see some of the good things about her.”

“Just remind us?”

“I’m thinking – and you probably won’t agree with this because I sense that you’re a firm supporter of the NUJ [National Union of Journalists] – mainly of her dealings with the unions.”

“How do you feel about her now?”

“I think she is a very brave woman.”

“Hitler was brave.”

“Yes, but… she was right about terrorism. She was right about the IRA.”

“Do you think Britain would be a better place if she’d never existed?”

“No. I think Britain benefited from her having been there. Britain was becoming so arthritic with labour restrictions.”

“Good Times, Bad Times is an unforgiving portrait of Rupert Murdoch.”

. . .

(p. 13) [Evans] has called Rupert Murdoch elitist, anti-democratic, and asserted that the Australian cares nothing about the opinion of others, so long as his business expands. This is the same man who refers to “the gratifying defeat of the Luddite unions by Rupert Murdoch”.

. . .

“So how do you feel about the Murdoch empire now?”

Evans pauses. “I’m not that familiar with the British… OK. Let’s take an alternative scenario. Murdoch never arrives. I manage to take control of The Sunday Times with the management buyout. Then I get defeated by the unions. The Independent wouldn’t be here. Rival papers survived because they got the technology. Thanks to Murdoch.”

For the full interview, see:

Robert Chalmers, Interviewer. “Harold Evans: ‘All I tried to do was shed a little light’.” The Independent on Sunday (Sun., June 13, 2010): 8 & 10-13.

(Note: free-standing ellipsis, between paragraphs, added; internal ellipses in original; italics in original; bracketed name added in place of “he.”)