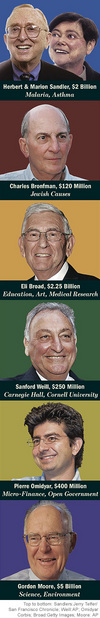

(p. A1) "If we give it away now, we’re going to do a good job with it, instead of leaving it to future generations of foundation folks," says Herbert M. Sandler, 74 years old. He and his wife, Marion, intend to donate the $2 billion they expect from the sale of the California savings and loan Golden West Financial Corp. before "we shuffle off this mortal coil."

The Sandlers’ plan, like Mr. Buffett’s $30 billion gift to the Gates foundation announced last month, exemplifies the changing pattern of U.S. philanthropy — and the (p. A8) Gates organization’s increasing influence over it. The charitable titans of today are unlike many of the old-school business bluebloods who sought to immortalize their names by setting up foundations that parceled out small gifts forever. Instead, some of America’s wealthiest moguls-turned-philanthropists — Eli Broad, Charles Bronfman, Lawrence Ellison, Michael Milken and Sanford Weill, among others — favor spending money faster, while retaining a high degree of control and demanding more accountability from the programs they fund.

. . .

By contrast, some of today’s tycoons increasingly limit the time frame, leaving tomorrow’s magnates to handle tomorrow’s problems. Mr. Bronfman, an heir to the Canadian liquor fortune, says he plans to exhaust the money in his $120 million foundation by 2020. He is spending at a $12 million to $14 million a year clip. "Why should I saddle the next generation with something I’m passionate about?" he says. "Let them have their own passions and do their own things." Mr. Bronfman, 75, believes in narrowly targeted goals — in his case, they include helping pay for young Jews to visit Israel. So far, his organization has had a hand in sending 112,000 people on such trips.

Mr. Milken, a financier who served two years in jail for securities fraud in the 1990s, funds medical research and K-12 education; he founded the Prostate Cancer Foundation in 1993 after being diagnosed with the disease himself. He said the six foundations he and his brother Lowell have established — which have funds of about $350 million — spend an average of 15% of their assets each year. Three of the six have attracted a total of $300 million in gifts from outside donors who, like Mr. Buffett, preferred supporting existing ventures to starting their own.

Mr. Milken said he negotiates with medical centers to make sure gifts go to research and clinical trials rather than overhead. In return, his foundations waive patent rights to any discoveries made as a result of their funding. "You can’t just write checks," he said. "You have to be actively involved. You have to introduce new management, marketing, other types of activities to empower medical research."

Mr. Sandler and his wife, Marion, have no patience for big foundations that spend 5% annually. "They are never going to give it [all] away," he says. Many foundations, he adds, "become bureaucratic."

He and his wife built their Oakland S&L, Golden West, from a small thrift into the nation’s second largest savings and loan by emphasizing lean operations and a laser-like focus on home lending. The couple, who are co-chief executives, recently agreed to sell the company to Wachovia Corp.

The Sandlers have already given heavily to start the Center for Basic Research in Parasitic Diseases at University of California at San Franciso’s medical school. The center focuses on Third World diseases neglected by major drug companies. Along with malaria, the family’s philanthropy has focused on finding treatment for the millions in South America afflicted by Chagas disease, a deadly insect-born ailment. A donor to the Democratic Party, Mr. Sandler has also backed progressive causes, including Human Rights Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, Acorn.

Mr. Sandler patterns his giving after the Gates foundation. He admires the Gates foundation’s program in Zambia, fighting malaria, and hopes to work together to replicate its methods in other countries. Like Mr. Gates, Mr. Sandler is looking for "gaps" in giving that he can fill, such as basic scientific research shunned by most big drug companies. Another interest: fighting asthma, which disproportionately afflicts the poor in inner-city America.

Mr. Sandler says he’s not afraid to take risks with his money, the same way he did in business. And he doesn’t want a foundation that, after his death, would spend frugally just to stay in business, or support causes far from his heart. "One prays that when we are going down the tubes, we will be giving that last million dollars," he says.

JOHN HECHINGER and DANIEL GOLDEN. "The Great Giveaway; Like Warren Buffett, a new wave of philanthropists are rushing to spend their money before they die." The Wall Street Journal (Sat., July 8, 2006): A1 & A8.

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/customer-reviews/078949647X/ref=cm_cr_dp_2_1/104-2835260-2878345?ie=UTF8&customer-reviews.sort%5Fby=-SubmissionDate&n=283155

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/customer-reviews/078949647X/ref=cm_cr_dp_2_1/104-2835260-2878345?ie=UTF8&customer-reviews.sort%5Fby=-SubmissionDate&n=283155

A vacuum tube used in guitar amplifiers, that was produced in the factory that Mike Matthews owned. Source of photo:

A vacuum tube used in guitar amplifiers, that was produced in the factory that Mike Matthews owned. Source of photo:  George B. Kaiser. Source of photo:

George B. Kaiser. Source of photo: