Source of graphic: http://www.ideachannel.com/Friedman.htm

Source of graphic: http://www.ideachannel.com/Friedman.htm

David Levy has noted in an email that at the reception to preview the new Friedman documentary, Gary Becker gave a great presentation on Milton Friedman, and it was a great shame that no one recorded it. I feel especially guilty, because I had thought of recording it, and had even brought a small camera that would have (badly) done the job. But the room was dark and crowded, and by the time the talk started, I was in conversation a long way from where Becker started speaking.

Levy suggests that maybe those of us who were there, should record our memories of what Becker said. I like that idea, and will record mine here.

Becker started out by saying to Bob Chitester that he wasn’t sure that the documentary did justice to Friedman. (Chitester was the producer, I think, of the original Free to Choose series, and a moving force behind the new Friedman documentary, to be first shown on PBS on January 29th, 2007.)

Becker mentioned that Friedman was a missionary. He would talk economics to anyone–if a taxi driver made a mistaken comment about economics, Friedman would set him straight.

Becker mentioned that while Friedman liked to argue about ideas, he never saw him be mean to anyone.

Becker mentioned that a friend of his taking Friedman’s price theory class (I think Becker may have said the friend was Gregory Chow?) asked Becker how he could keep asking questions in Becker’s class, when Friedman would keep showing the ways in which Becker was mistaken.

Becker mentioned that he talked to Friedman a few days before his death, and that they even talked a little economics.

Becker emphasized that Friedman had been both a great economist, and had made an enormous difference in the world, in particular in making the world more free.

Some background: Becker spoke about Friedman at two sessions at the Allied Social Sciences Association meetings in Chicago in early January. One was in the afternoon (about 2:30 PM?) of January 5, 2007, and also included Robert Lucas, and Tom Sargent. I missed that session because I wanted to attend a session featuring the research program of Robert Fogel on longevity. The second session, at 6:00 – 7:30 PM on Sat., January 6, 2007 was at a reception sponsored by the University of Chicago to preview the new documentary on Friedman. I attended this reception through Becker’s presentation, but did not stay for the documentary preview. My friend Luis Locay attended both sessions, and told me that some, but not all, of the stories Becker told were similar in both sessions. Locay also mentioned that Becker appeared to get more choked-up at the session on January 5, 2007.

David Brooks. Source of photo: online version of the NYT commentary cited below.

David Brooks. Source of photo: online version of the NYT commentary cited below.

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of graphic:

Source of graphic:  CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.

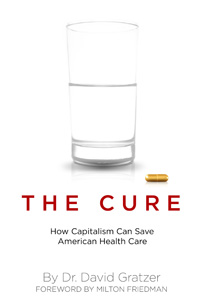

CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below. Source of book image:

Source of book image: