Schumpeter famously stated that creative destruction is "the essential fact" about capitalism. Was he right?

To determine what is "the essential fact" you need to first answer the question "essential for what purpose?" If the purpose is "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" then I think you can show that creative detruction is indeed the essential fact about capitalism; in the key sense that with creative destruction you have a form of capitalism that is best able to enhance "live, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

The Terminator famously said "Come with me, if you want to live!" ("Terminator 2: Judgment Day," 1991). Life is a choice. You can choose death instead. Most people, most of the time, choose life. But there are examples of choosing death. E.g., Leon Kass, an oft-quoted "expert" on medical ethics issues, is against current efforts to lengthen the human life span:

(p. D4) While an anti-aging pill may be the next big blockbuster, some ethicists believe that the all-out determination to extend life span is veined with arrogance. As appointments with death are postponed, says Dr. Leon R. Kass, former chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics, human lives may become less engaging, less meaningful, even less beautiful.

“Mortality makes life matter,” Dr. Kass recently wrote. “Immortality is a kind of oblivion — like death itself.”

That man’s time on this planet is limited, and rightfully so, is a cultural belief deeply held by many. But whether an increasing life span affords greater opportunity to find meaning or distracts from the pursuit, the prospect has become too great a temptation to ignore — least of all, for scientists.

“It’s a just big waste of talent and wisdom to have people die in their 60s and 70s,” said Dr. Sinclair of Harvard.

(And there’s the occasional hermit, like the unibomber, who chooses to live a brutish life without electricity and indoor plumbing.) So long as I, Arnold, and our compatriots, are allowed an island somewhere to peacefully pursue life, I do not much care what Leon and his friends do. My argument, and the book I am writing on creative destruction, are not written for Leon. They are written for all those who choose life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The NYT quote related to Leon Kass’s praise of mortality, is from p. D4 of:

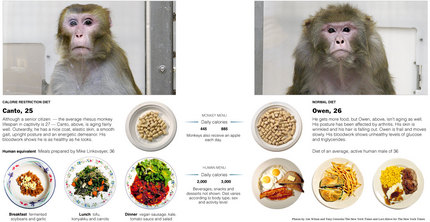

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

One of the dogs cured of melanoma by a new vaccine. Source of photo:

One of the dogs cured of melanoma by a new vaccine. Source of photo:  Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.