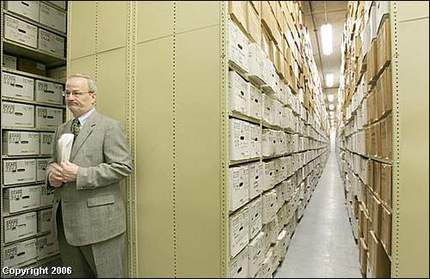

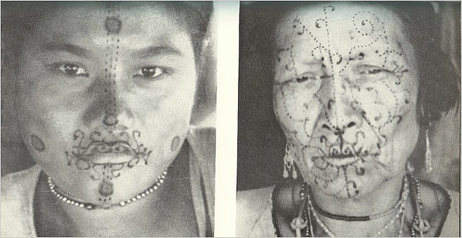

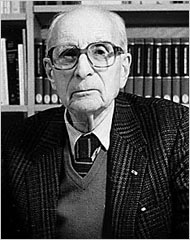

1935 photos of painted Caduveo women from Claude Lévi-Strauss Structural Anthropology. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

1935 photos of painted Caduveo women from Claude Lévi-Strauss Structural Anthropology. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

I remember in a philosophy class back in the 1970s, the philosopher Stephen Toulmin mentioning that he had once attended a conference with the famed anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. For a long while Lévi-Strauss sat in silence. Finally he stirred himself to speak, and Toulmin wondered what wisdom the great man would pronounce.

His comment was something like: "It is hot in here. Will someone open a window?"

News of the death of the philosopher Richard Rorty on June 8 came as I was reading about a small Brazilian tribe that the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss studied in the 1930s. A strange accident, a haphazard juxtaposition — but for a moment this pragmatist philosopher and a fading tribal culture glanced against each other, revealing something unusual about the contemporary scene.

. . .

For Mr. Rorty, the importance of democracy is that it creates a liberal society in which rival truth claims can compete and accommodate each other. His pragmatism was postmodern, tolerant to a fault, its moral and progressive conclusions never appealing to a higher authority.

. . .

The Caduveo founding myth recounts that, lacking other gifts at the moment of creation, the tribe was given the divine right to exploit and dominate others.

. . .

But there was also something else about this tribe that drew Mr. Lévi-Strauss’s attention: “It was a society remarkably adverse to feelings that we consider as being natural.” Its members disliked having children. Abortion and infanticide were so common that the only way the tribe itself could continue was by adoption, and adoption — more properly called abduction — was traditionally implemented through warfare. The tribal disdain for nature extended into its active denigration of hair, agriculture, childbirth and even, perhaps, representational art.

. . .

In reasoning one’s way into pragmatism, in minimizing the importance of natural constraints and in dismissing the notion of some larger truth, the tendency is to assume that as different as we all are, we are at least prepared to accommodate ourselves to one another. But this is not something the Caduveo would necessarily have gone along with. Mr. Rorty’s outline of what he called “the utopian possibilities of the future” doesn’t leave much room for the kind of threat the Caduveo might pose, let alone other threats, still active in the world.

One tendency of pragmatism might be to so focus on the ways in which one’s own worldview is flawed that trauma is more readily attributed to internal failure than to external challenges. In one of his last interviews Mr. Rorty recalled the events of 9/11: “When I heard the news about the twin towers, my first thought was: ‘Oh, God. Bush will use this the way Hitler used the Reichstag fire.’ ”

If that really was his first thought, it reflects a certain amount of reluctance to comprehend forces lying beyond the boundaries of his familiar world, an inability fully to imagine what confrontations over truth might look like, possibly even a resistance to stepping outside of one’s skin or mental habits.

But in this too the Caduveo example may be suggestive. As Mr. Lévi-Strauss points out, neighboring Brazilian tribes were as hierarchical as the Caduveo but lacked the tribe’s sweeping “fanaticism” in rejecting the natural world. They reached differing forms of accommodation with their surroundings. The Caduveo, refusing even to procreate, didn’t have a chance. They survive now as sedentary farmers. Such a fate of denatured inconsequence may eventually be shared by absolutist postmodernism. The Caduveo’s ideas weren’t useful, perhaps. Some weren’t even true.

For the full commentary, see:

EDWARD ROTHSTEIN. "CONNECTIONS; Postmodern Thoughts, Illuminated by the Practices of a Premodern Tribe." The New York Times (Mon., June 18, 2007): B3.

(Note: ellipses added.)

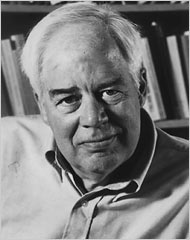

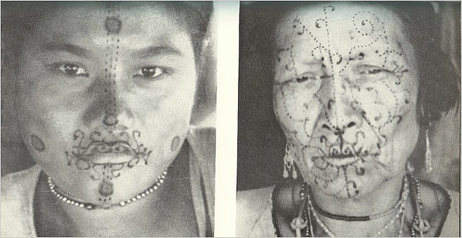

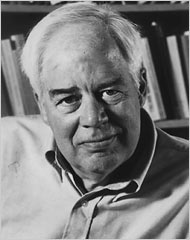

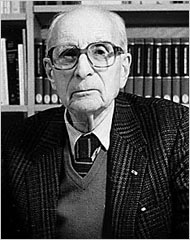

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

“Tests of jars found in the ruins of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico confirmed the presence of theobromine, a cacao marker.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Tests of jars found in the ruins of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico confirmed the presence of theobromine, a cacao marker.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.