Source of graph: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article quoted and cited below.

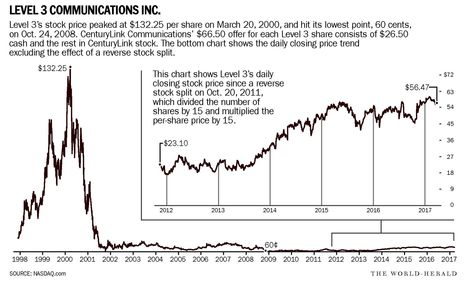

(p. 1D) Thomas Dowd and hundreds of other Omahans soon will be digging out their Level 3 Communications Inc. stock records. • The reason: This week, Level 3 shareholders are voting to sell the company to Century Link Communications. • The sale marks the end of an investment saga that began 20 years ago with hopes of riches but ended with big losses for most shareholders, despite the efforts of some of Omaha’s biggest names in business. • “It was a very bad experience,” said Dowd, a retired attorney and former director of the Metropolitan Utilities District. “It’s just one purchase at a time, and you think everything’s going good and then, bam! Anyway, lesson learned.” • Although his loss was “substantial,” he said, it didn’t disrupt his lifestyle, and he figures he’s better off than shareholders who lost their retirement savings or other vital funds. He’s still a Level 3 shareholder and will get some cash and Century Link shares in the sale, which is scheduled for September [2017].

(p. 4D) But it works out to about $4.43 for shares he bought years ago, some of them costing more than $100.

. . .

On March 20, 2000, someone sold and someone bought Level 3 shares for $132.25, a price that made the company’s publicly traded stock worth nearly $20 billion. By 2002, the price had nearly collapsed, putting most shareholders into the red.

Level 3 might have an information highway, but its toll system wasn’t collecting enough to earn a profit. It was clear that the nation had a “bandwidth glut,” a huge overcapacity of fiber networks.

Level 3 had installed its network, at an eventual cost of $14 billion, and could cheaply add more lines by stringing extra cable through its conduits.

But others had built networks, too, and the demand for bandwidth wasn’t growing as Crowe had hoped. Researchers also found ways to send more data along existing fibers, meaning greater capacity along existing lines.

Most of the new fiber networks were unused, or “dark.” Only a fraction of fibers in the buried bundles were “lit” by the light waves that carried digital communications and brought in revenue for companies like Level 3.

The supply of fiber far outran the demand, and Level 3’s losses mounted, along with its stock price. Investors lost confidence that the company would begin making profits anytime soon. In fact, that didn’t happen until 2014.

. . .

Dowd, the retired attorney, said he held onto the shares because it didn’t seem worthwhile to sell at the lower prices and he figured someone would buy the company and he would get some of his money back.

“I always thought Walter Scott was going to pull a rabbit out of the hat,” he said. “He never did.”

For the full story, see:

STEVE JORDON. “END OF THE LINE FOR LEVEL 3; Omaha-born company, which laid fiber-optic cable, will cease to exist.” Omaha World-Herald (Sun., March 12, 2017): 1D & 4D.

(Note: ellipses added.)