(p. 1) In proposing a tax-cut law last week, Finance Minister Christine Lagarde bluntly advised the French people to abandon their “old national habit.”

“France is a country that thinks,” she told the National Assembly. “There is hardly an ideology that we haven’t turned into a theory. We have in our libraries enough to talk about for centuries to come. This is why I would like to tell you: Enough thinking, already. Roll up your sleeves.”

Citing Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” she said the French should work harder, earn more and be rewarded with lower taxes if they get rich.

. . .

(p. 9) The government’s call to work is crucial to its ambitious campaign to revitalize the French economy by increasing both employment and consumer buying power. Somehow Mr. Sarkozy and his team hope to persuade the French that it is in their interest to abandon what some commentators call a nationwide “laziness” and to work longer and harder, and maybe even get rich.

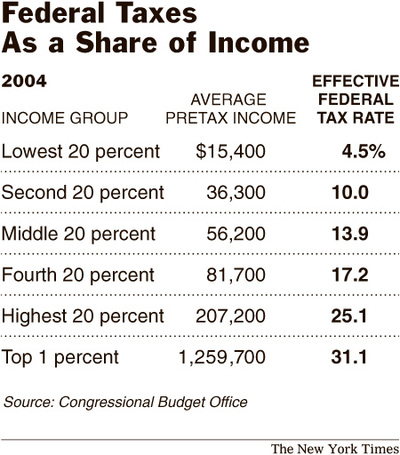

France’s legally mandated 35-hour work week gives workers a lot of leisure time but not necessarily the means to enjoy it. Taxes on high-wage earners are so burdensome that hordes have fled abroad. (Mr. Sarkozy cites the case of one of his stepdaughters, who works in an investment-banking firm in London.)

In her National Assembly speech, Ms. Lagarde said that there should be no shame in personal wealth and that the country needed tax breaks to lure the rich back.

. . .

“We are seeing an important cultural change,” said Eric Chaney, chief economist for Europe for Morgan Stanley. “Working families in France want to be richer. Wealth is no longer a taboo. There’s a strong sentiment in France that people think prices are too high and need more money. It’s not a question of thinking or not thinking.”

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

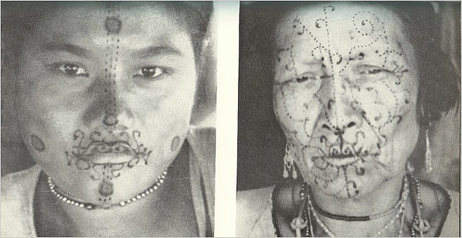

I used to have a photo at the top of Sarokozy running; in contrast to this picture of Mitterrand walking. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

I used to have a photo at the top of Sarokozy running; in contrast to this picture of Mitterrand walking. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

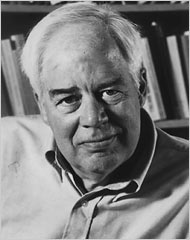

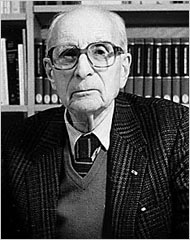

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Rorty on left; Lévi-Strauss on right. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

(Note: ellipsis in Rearden quote was in original; the other two ellipses were added.)

(Note: ellipsis in Rearden quote was in original; the other two ellipses were added.)