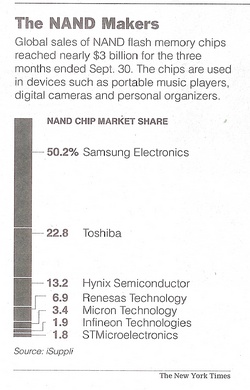

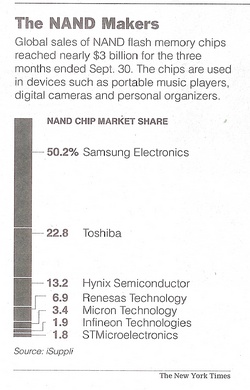

Graph source: page C6 of article cited below.

Graph source: page C6 of article cited below.

(C1) YOKKAICHI, Japan – Nestled in a valley in central Japan, surrounded by forested hills and terraced rice paddies, is one of the world’s most sophisticated – and secretive – semiconductor plants. Inside the windowless plant, built by the Japanese electronics maker Toshiba, tiny cranelike robots shuffle along automated production lines, moving stacks of silicon wafers the size of dinner plates. Masked technicians watch as rows of tall machines grind the wafers, etch circuits on their surfaces and cut them into tiny rectangular computer chips. Inside, visitors are allowed to peek through windows at only a small part of the factory floor. Toshiba is anxious to guard the secrets beyond because it needs them to wage one of the most ferocious battles in today’s electronics industry, for control of the fast-growing market for the advanced memory chips at the heart of portable music devices like the Apple iPod Nano. The fight pits Toshiba and its partner, SanDisk of Sunnyvale, Calif., a maker of memory cards, against Samsung Electronics of South Korea. Both camps are spending billions to build new factory lines, hire engineers and develop more powerful chips in a bid to gain supremacy. The chips, called NAND flash memory chips, differ from earlier computer memory chips in that data on them can be easily erased and replaced and they can store data even after the power is turned off. That makes them like miniature hard-disk drives, only much more durable because they lack moving parts. The newest flash memory chips are the size of a fingernail and can store two gigabytes, the equivalent of every word and image printed in nine years of a newspaper. While Toshiba invented the chips more than a decade ago, Samsung has seized the lead with bigger production volumes and lower prices. In the three months that ended in September, Samsung had a market share of 50.2 percent of the $2.97 billion in total global NAND sales, ac- (C6) cording to iSuppli, a market research firm based in El Segundo, Calif. Toshiba’s share was 22.8 percent. SanDisk is not included in iSuppli’s figures because it does not sell its chips, but instead uses them all in its own memory products. . . . At Toshiba’s Yokkaichi plant, there is a palpable determination to catch up with the larger Korean rival. Engineers work in shifts around the clock to speed up development and production of new chips. Noriyoshi Tozawa, the plant’s manager, said he kept workers on their toes with little reminders of darker times. One is an elevator that has been kept out of use since 2001; a sign on the doors says that it was turned off after a crash in computer chip prices almost forced the closure of the plant, which used to produce DRAM, another type of memory chip. "You have to always be at the leading edge to stay alive in this industry," Mr. Tozawa. "We know what it’s like to lose."

To read full article, see: MARTIN FACKLER. "Among Makers of Memory Chips for Gadgets, Fierce Scrum Takes Shape." The New York Times (Mon., December 12, 2005): C1 & C6.

scrum: "a rugby play in which the forwards of each side come together in a tight formation and struggle to gain possession of the ball when it is tossed in among them" Definition source: http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=scrum&x=6&y=21

1999 photo of Drucker from NYT online article cited below.

1999 photo of Drucker from NYT online article cited below. Source of photo: WSJ online version of article quoted and cited below.

Source of photo: WSJ online version of article quoted and cited below.