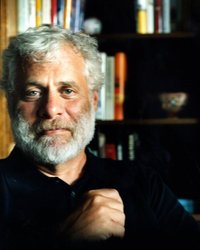

Ray Kurzweil. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. C12) Inventor and entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil is a pioneer in artificial intelligence–the principal developer of the first print-to-speech reading machine for the blind, and the first text-to-speech synthesizer, among other breakthroughs. He is also a writer who explores the future of information technology and how it is changing our world.

In a wide-ranging interview, Mr. Kurzweil and The Wall Street Journal’s Alan Murray discussed advances in artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and what it means to be human. Here are edited excerpts of their conversation:

. . .

MR. MURRAY: What about life expectancy? Is there a limit?

MR. KURZWEIL: No. We’re constantly pushing back life expectancy. Now it’s going to go into high gear because of the inherent exponential progression of information technology. According to my models, within 15 years we’ll be adding more than a year to your remaining life expectancy each year.

MR. MURRAY: So if you play the odds right, you never hit the endpoint.

MR. KURZWEIL: Right. If you can hang in there for another 15 years, we could get to that point.What Is Human?

MR. MURRAY: What does it mean to be human in a post-2029 world?

MR. KURZWEIL: It’s a slippery slope. But we’ve already gone down that slope. I’ve talked to people who have neural implants in their brain, for Parkinson’s, and I’ve asked them, “Are you still human? Are you less human?”

Generally speaking, they say, “It’s part of me.” And they’re very proud of it, because it restored their human functionality.

For the full interview, see:

Alan Murray, interviewer. “Man or Machine? Ray Kurzweil on how long it will be before computers can do everything the brain can do.” The Wall Street Journal (Fri., June 29, 2012): C12.

(Note: ellipsis added; bold in original.)