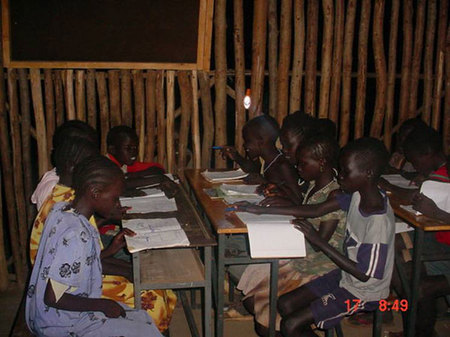

Is it Glacier Creek, or Big Thompson River? Source of photo: me.

Is it Glacier Creek, or Big Thompson River? Source of photo: me.

On May 17, 2007, in Estes Park, Colorado, I was the co-leader of a "two hour" hike with 15 Montessori middle-schoolers from Omaha, Nebraska. At some point what we were seeing didn’t seem to correspond with what our roughly drawn YMCA map told us we should be seeing–we worried that we had taken a wrong turn and were lost.

II we were on course, then the water beside us should be Glacier Creek. If we were lost, then it was probably Big Thompson River. (It’s appearance didn’t help–it looked a bit larger than a creek, but a lot smaller than a ‘big river.’)

The first person I found to ask was a tourist who admitted upfront that she was extremely uncertain about where we were. She pulled out a modest map, and pointed to where she thought we might be, which was along the Big Thompson River.

Seeking confirmation, I apologetically interrupted a fellow teaching his girl-friend how to fly fish. This fellow was dressed as an outdoors-man, and exuded confidence. He talked about hiking on a glacier the day before. He helpfully strode back to his SUV with me and pulled a detailed, authoritative-looking map. With no doubt, he pointed on the map to where we were, on Glacier Creek, as I had hoped. As we walked back to where he had been fishing, he pointed in the direction that we had been hiking, and said that without question, we should continue to hike in that direction.

The scenery was fantastic, but Cindy began to worry whether we were going in the right direction, pointing out that there didn’t seem to be any opening in the mountains in the direction in which we were supposing the YMCA camp should be. I agreed with her observation, but said that there must be some non-obvious route, because the fellow who pointed us in this direction had exuded credibility.

We finally got to a small museum. There, an old park service employee asked where we were from. When I said "Omaha" he jokingly asked if knew his old friend Warren Buffet? He told us that he had lived in this area all his life, and that we were definitely walking along Big Thompson River. Then he tried to draw a map to show us how to get back. He scratched his head, discarded his first attempt, and started trying again. Then he asked us (again) where we were from? At this point, I was really worried.

But his second attempt at a map was a good one–it got us back to the YMCA camp.

Maybe we should look for advice from those who are self-critical, as the old man was, rather than from those who exude undoubting self-confidence, as the fly fisherman did? (Or maybe the key was local credentials?)

Maybe, I made a mistake that Christensen and Raynor warn against in their The Innovator’s Solution: looking at charisma and confidence as signs of who to follow. (In fairness to myself, at the time, I didn’t have much else to go on.)

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.