The author of the commentary quoted below is the head lawyer for Intel. I believe that the evidence is strong that patents can provide strong incentives for innovation. But the devil is in the details. I have not studied the Patent Reform Act of 2007, so I am not sure whether, overall, it is an improvement over the current rules. But the case for reform is strong, and the topic is one that highly deserves further research.

(p. A15) The U.S. patent system is beginning to show its age; outpaced by the swift evolution of technology and commerce, it increasingly favors speculators over innovators, impeding innovation and economic growth. Fortunately, the bipartisan "Patent Reform Act of 2007," introduced in both the House and Senate, would improve the process for granting patents, and rebalance court rules and procedures to ensure fair treatment when patents wind up in litigation. The Senate Judiciary Committee will take up S.1145 today.

Congress needs to pass this bill, during this session, as the need for reform is clear. Nationwide, the number of patent lawsuits nearly tripled between 1991 and 2004, and the number of cases between 2001 and 2005 grew nearly 20%. Until 1990, only one patent damages award exceeded $100 million; more than 10 judgments and settlements were entered in the last five years, and at least four topped $500 million. One recent decision topped $1.5 billion.

The number of questionable, loosely defined patents, moreover, is rising. One company holds patents that it claims broadly cover current technologies that allow people to make phone calls over the Internet. Another has staked a claim on streaming video over the Internet generally and has pursued colleges for royalties on their distance-learning programs. In 2002, a five-year-old boy patented a method of swinging on a swing.

Unfortunately, under current law, parties that want to innovate in areas covered by questionable patents have only two options, both of them bad: an ineffective, rarely used re-examination process, or litigation — the average cost of which is, by some estimates, $4.5 million. This impedes innovation, as the FTC noted: "One firm’s questionable patent may lead its competitor to forgo R&D in the areas that the patent improperly covers."

For the full commentary, see:

BRUCE SEWELL. "Patent Nonsense." The Wall Street Journal (Thurs., July 12, 2007): A15.

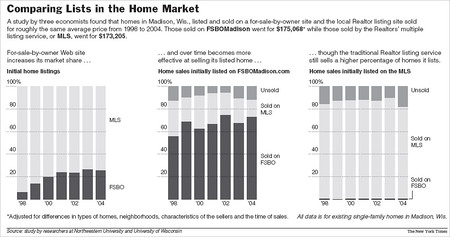

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.