Manuel and mother Mercedes of the entrepreneurial Miranda family, inspect the corn flatbread called "arepa." Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Manuel and mother Mercedes of the entrepreneurial Miranda family, inspect the corn flatbread called "arepa." Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Immigrant entrepreneurship contributes to the vitality and dynamism of New York and the nation. Note the graphic at the bottom of this entry shows that employment increases in the same areas of the city in which immigrant entrepreneurship is thriving.

Manuel A. Miranda was 8 when his family immigrated to New York from Bogotá. His parents, who had been lawyers, turned to selling home-cooked food from the trunk of their car. Manuel pitched in after school, grinding corn by hand for traditional Colombian flatbreads called arepas.

Today Mr. Miranda, 32, runs a family business with 16 employees, producing 10 million arepas a year in the Maspeth section of Queens. But the burst of Colombian immigration to the city has slowed; arepas customers are spreading through the suburbs, and competition for them is fierce. Now, he says, his eye is on a vast, untapped market: the rest of the country.

. . .

“Immigrants have been the entrepreneurial spark plugs of cities from New York to Los Angeles,” said Jonathan Bowles, the director of the Center for an Urban Future, a private, nonprofit research organization that has studied the dynamics of immigrant businesses that turned decaying neighborhoods into vibrant commercial hubs in recent decades. “These are precious and important economic generators for New York City, and there’s a risk that we might lose them over the next decade.”

A report to be issued by the center today highlights both the potential and the challenge for cities full of immigrant entrepreneurs, who often face language barriers, difficulties getting credit, and problems connecting with mainstream agencies that help businesses grow. The report identifies a generation of immigrant-founded enterprises poised to break into the big time — or already there, like the Lams Group, one of the city’s most aggressive hotel developers, or Delgado Travel, which reaps roughly $1 billion in annual revenues.

In Los Angeles, at least 22 of the 100 fastest-growing companies in 2005 were created by first-generation immigrants. In Houston, a telecommunications company started by a Pakistani man topped the 2006 list of the city’s most successful small businesses.

But even in those cities and New York, where immigrant-friendly mayors have promoted programs to help small business, the report contends that immigrant entrepreneurs have been overlooked in long-term strategies for economic development.

. . .

Now, some children of the early influx are trying to build on their parents’ success — success that itself has increased the cost of doing business, by driving up rents and creating congestion.

One example is Jay Joshua, a Manhattan company that designs souvenirs and then has them manufactured in Asia and imported. Jay Chung, who arrived from South Korea in 1981 as a graduate student in design, started printing his computer-graphic designs for New York logos and peddling them to local T-shirt shops. His company is now one of the city’s leading suppliers of tourist items, from New York-loving coffee mugs to taxicab Christmas ornaments.

Mr. Chung’s son Joshua, 26, who was 3 when he immigrated, joined the company after studying business management in college, and recently helped land orders for a new line of Chicago souvenirs. But frustration mixes with pride when the Chungs, both American citizens now, discuss the company’s growth.

“It’s really hard to conduct a business over here as a wholesaler,” Mr. Chung said in the company’s West 27th Street showroom, chockablock with samples. “We get a ticket every 20 minutes, no matter what. We need more convenient places with less rent, less traffic.”

Thirty years ago their wholesale district was desolate. Now hundreds of Korean-American importers are there, said Jay Chung, who is a leader of the local Korean-American business association. They face a blizzard of parking tickets and high commercial rents — nearly $20,000 a month for 1,400 square feet, he said.

For the full story, see:

NINA BERNSTEIN. "Immigrant Entrepreneurs Shape a New Economy." The New York Times (Tues., February 6, 2007): C13.

(Note: the ellipses are added.)

The author of the New York Times article has contributed to a New York Times digital video clip that is based on the article and is entitled "Immigrant Entrepreneurs: A Tour of One Bustling Ethnic Enclave."

Entrepreneur father Jay and son Joshua own a firm that supplies New York City souveniers. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Entrepreneur father Jay and son Joshua own a firm that supplies New York City souveniers. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited above.

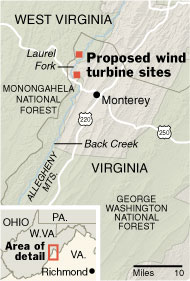

The location in Highland County, Virginia where 19 wind turbines are planned. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

The location in Highland County, Virginia where 19 wind turbines are planned. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below. Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

JetBlue passengers during the 8 and a half hours that they were stranded on the tarmac without being allowed to leave the plane on Weds., February 14th. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

JetBlue passengers during the 8 and a half hours that they were stranded on the tarmac without being allowed to leave the plane on Weds., February 14th. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below. JetBlue planes on Mon., February 19th at JFK airport. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

JetBlue planes on Mon., February 19th at JFK airport. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Rats for dinner in Zimbabwe. Source: online CNN article cited above.

Rats for dinner in Zimbabwe. Source: online CNN article cited above.

Entrepreneur father Jay and son Joshua own a firm that supplies New York City souveniers. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Entrepreneur father Jay and son Joshua own a firm that supplies New York City souveniers. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Two views of the new parking meters in Redwood, California. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Two views of the new parking meters in Redwood, California. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Sensors such as the one embedded in the San Francisco street on the left, could eventually be used to help track parking violators, as imagined in the fictional picture on the right. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Sensors such as the one embedded in the San Francisco street on the left, could eventually be used to help track parking violators, as imagined in the fictional picture on the right. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Patrick Logue the former real estate agent and current dog trainer. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Patrick Logue the former real estate agent and current dog trainer. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.