Source of book image: http://images.barnesandnoble.com/images/7770000/7775266.jpg

Source of book image: http://images.barnesandnoble.com/images/7770000/7775266.jpg

When Ameritrade founder Joe Ricketts spoke to my Executive MBA class a few years ago, I mentioned to him that I had heard from Bob Slezak that Ricketts was a fan of Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma. Ricketts said that was true, but that the recent business book that he was most enthused about was Jim Collin’s Good to Great.

Ricketts is not alone. Good to Great has become a business classic since it came out. Recently I finally got around to reading it.

Well, I think it’s good, but not quite great. I like the empirical, inductive methodology mapped out at the beginning. And some of the conclusions ring true. For example the importance of facing the "brutal facts." And the importance of developing a thought-out "hedgehog" concept. And the importance of getting the right people on the bus. And the importance of slowly, consistently building momentum.

But I’ve got some big bones to pick, too.

Maybe the biggest "bone" is Collins’ assumption that our goal should be the survival and greatness of a firm. Instead of almost viewing firms as ends in themselves, why can’t we view firms as vehicles for getting great things done?

Maybe great things can be done through firms that last and are lastingly great. Or maybe great things can be done by shooting star firms, that are glorious while they last, but don’t last long. Collins says it must be the former. But either way works for me.

A smaller "bone" is the conclusion that "level 5" leaders tend to be modest. Well maybe. But some of that conclusion is derived from Collins’ defining "great" in terms of high growth of stock value. A modest leader will be unappreciated by Wall Street, and her company’s stock value will show higher growth when she succeeds. But has she thereby accomplished more than if she had built exactly the same company, but been more transparent and enthused about the company’s future prospects, and hence generated more realistic expectations from Wall Street? Remember, the value of a stock grows, not by the company doing well, but by it doing better than investors expected. (On this issue, Collins should read the first couple of chapters of Christensen and Raynor’s The Innovator’s Solution.)

But don’t get me wrong: this is a very good book. Those interested in how the capitalist system works, should read it, as should those who want to manage well.

The book is:

Collins, Jim. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap. And Others Don’t. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Bob Chitester. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Bob Chitester. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

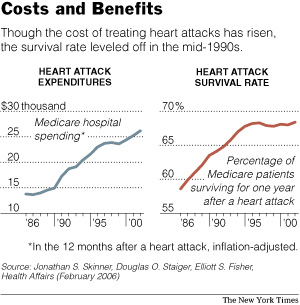

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.