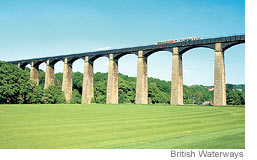

Pontcysyllte aqueduct. Source of image: online version of WSJ article quoted and cited below.

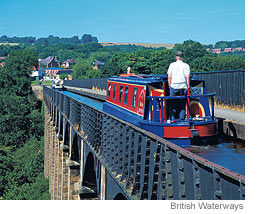

(p. P12) Of all the stupendous engineering structures produced by the Industrial Revolution, the Pontcysyllte is one of the most extraordinary: a ribbon of water in the sky. A narrow cast-iron water-filled trough, over 1,000 feet long, strides out across a steep-sided Welsh valley on a series of slender stone piers. Canal boats drift across, reaching a height of 126 feet above the valley floor. I first made this trip as a child and it was exhilarating and terrifying at the same time. It still is. Because while there is a towpath and handrail on one side of you, on the other there is nothing but the thin lip of the trough, rising to only a few inches above the waterline. It does not look strong enough. You feel you are going to plunge over the edge.

This is one of those marvels of engineering and architecture that really should not exist. Economically, it never made any sense. A product of Britain’s canal-building mania of the 1790s, it opened in 1805 and found itself on a route that went nowhere much, and then stopped. Having been built, it should not logically have survived. It is sited on a truncated stretch of waterway, a puzzling fragment of a much larger, never-completed scheme. This was known as the Ellesmere Canal, intended to link the mighty rivers of Mersey and Severn via the coal and iron ore mines of North Wales. But no sooner had engineers Thomas Telford and William Jessop completed this hugely ambitious structure — along with other expensive aqueducts and tunnels, piercing the hills and leaping the valleys to get to this point — than financial reality took hold and the project was halted. Commercial boat traffic on the inconclusive sections that were built was always light, and had ceased by 1939. The waterway was officially abandoned to navigation in 1944. But salvation was at hand.

It, and its matchless aqueduct, survived for two reasons. Almost by accident, it provided a fresh water supply from the Welsh hills to the towns and cities of northwest England. And it became an early campaign victory, a symbol, for Britain’s nascent waterways preservation movement in the 1940s. The canal network was being rediscovered by a generation of postwar nostalgists, alert both to industrial heritage and to the fast-vanishing gypsy-like lifestyle of the traditional boating families in their “narrow boats” (never called barges).

For the full commentary, see:

Hugh Pearman. “MASTERPIECE; A Marvel That Shouldn’t Exist; In Wales, a fusion of architecture, engineering and nature.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., February 4, 2006): P12.

Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited above.