If you were standing amongst a herd of antelope when a dangerous predator arrived, you would not see the antelope defending themselves against the predator. What you would see would be their white rear ends disappearing in the distance.

Last July in Wichita I heard some executives from Koch Industries talking about Market-Based Management. A couple of them mentioned Koch’s stands in defense of the free market. As a result of these efforts, Koch Industries has become the target of many agencies of the government and of groups opposed to the free market. Once or twice I heard an executive say something like: ‘it would have been a lot easier if we had just painted our butts white and run with the antelope.’

Schumpeter thought that those in business would not defend the fortress of capitalism (CSD, p. 142). And the evidence suggests that Schumpeter was mainly right. But we can hope that there are enough exceptions, in unpretentious places like Wichita, to keep the fortress standing.

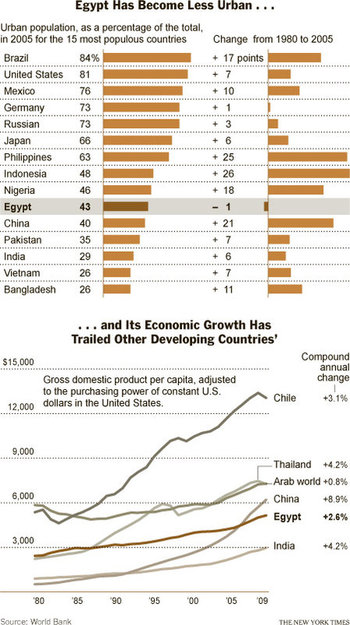

(p.A15) Years of tremendous overspending by federal, state and local governments have brought us face-to-face with an economic crisis. Federal spending will total at least $3.8 trillion this year–double what it was 10 years ago. And unlike in 2001, when there was a small federal surplus, this year’s projected budget deficit is more than $1.6 trillion.

Several trillions more in debt have been accumulated by state and local governments. States are looking at a combined total of more than $130 billion in budget shortfalls this year. Next year, they will be in even worse shape as most so-called stimulus payments end.

For many years, I, my family and our company have contributed to a variety of intellectual and political causes working to solve these problems. Because of our activism, we’ve been vilified by various groups. Despite this criticism, we’re determined to keep contributing and standing up for those politicians, like Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who are taking these challenges seriously.

For the full commentary, see:

CHARLES G. KOCH. “Why Koch Industries Is Speaking Out; Crony capitalism and bloated government prevent entrepreneurs from producing the products and services that make people’s lives better.” The Wall Street Journal (Tues., MARCH 1, 2011): A15.

Koch’s book is:

Koch, Charles G. The Science of Success: How Market-Based Management Built the World’s Largest Private Company. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007.