Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted, and cited, below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted, and cited, below.

(p. B1) In a move that could mark the beginning of a nuclear-power revival, a New Jersey-based energy company today plans to submit an application to build and operate two new reactors. The request, the first submitted to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 31 years, comes from an unlikely source: NRG Energy Inc., a company that has never before built a nuclear plant.

The application — for a two-reactor addition to the company’s existing South Texas nuclear station — could offer the first full test of the nuclear agency’s new licensing process, which has been under development since the 1980s. The new process allows companies to submit a single application for a construction permit and conditional operating license, eliminating the risk that a firm could build a plant but not be allowed to run it.

. . .

(p. B2) . . . , the industry has regained momentum, partly because other forms of power generation have continued to show significant flaws. Coal-fired plants undermine efforts to combat global warming. Many natural-gas-fired plants rely on a fuel with volatile prices. And renewable energy mostly comes from intermittent forces like wind, rain and sunlight.

This first application comes from a somewhat unlikely source; NRG is a so-called "merchant generator," a company that makes electricity and sells it on the open market. NRG has never built a nuclear plant, and because it doesn’t own a utility, has no ratepayers to whom it could bill the estimated $5.5 billion to $6 billion expense.

"We’re like the uncola," says David Crane, NRG chief executive in Princeton, N.J.

. . .

So far, it appears merchant generators think Texas provides the most promising market. Deregulation in that state has resulted in a sharp run up in wholesale power prices since 2004. A recent decision by Dallas-based TXU to abandon efforts to build eight coal-fired plants could result in shrinking electricity reserves in the coming years, creating an environment receptive to operators looking to bring large units online and sell such units’ full output.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: ellipses added.)

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

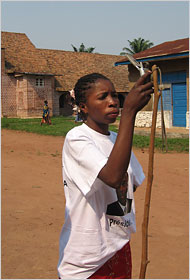

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above. "Micheline Kapinga of Kamponde, Congo, uses a cellphone on the only site in the village that is sometimes able to capture a signal." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

"Micheline Kapinga of Kamponde, Congo, uses a cellphone on the only site in the village that is sometimes able to capture a signal." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Genentech CEO Dr. Arthur D. Levinson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Genentech CEO Dr. Arthur D. Levinson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited above.