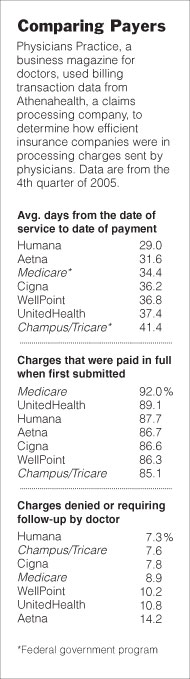

Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

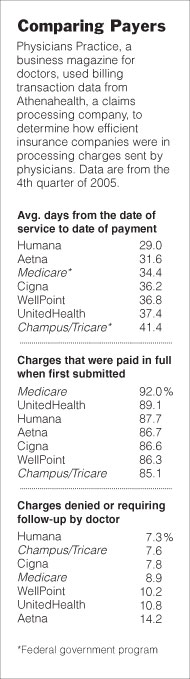

What is noteworthy in the table above is not the differences in delays in paying. What is noteworthy is that the fastest payer still takes a month to pay.

(p. C1) Few things rankle a doctor more than an insurance company’s saying it cannot find a claim for medical services. Particularly when there is even a signed return receipt to document delivery of the bill.

"We actually had the little green card to show who signed for the dang thing," said Elizabeth Wertz, chief executive of the Pediatric Alliance, a large group of Pittsburgh doctors. "We sent it by certified mail. The insurance company said they didn’t have it."

The claim was for several thousand dollars, according to Ms. Wertz, who declined to identify the company, a large regional insurer, for fear of making it more difficult to wrangle payments. It is a problem known to many doctors as they struggle to balance the rising cost of providing patient care with what they see as a reluctance by some powerful insurers to pay promptly.

Pediatric Alliance’s 37 doctors are among the 7,000 physicians, nurse practitioners and other health care providers around the country who are clients of the claims-processing company Athenahealth, which plans today to present a rare warts-and-all look at how well — or not — the nation’s seven biggest health insurers pay their bills.

Not well enough, in many cases, according to the data and to experts who say the survey provides the most comprehensive look yet at the state of accounts payable vs. accounts receivable in the nation’s health care system.

Tardiness or refusal to pay what doctors consider legitimate medical claims may add as much as 15 to 20 percent in overhead costs for physicians, forcing them to pursue those claims or pass along the costs to other patients, according to Jack Lewin, a family doctor who is chief executive of the California Medical Association, a professional group of 35,000 physicians.

. . .

(p. C10) Athenahealth, which says it collected $1.8 billion on behalf of its physician clients last year, is among the biggest of several thousand companies that help doctors and hospitals get paid by editing their claims and helping them to deal with difficult cases. Health care providers who can afford such services say they have become a necessary part of doing business.

In the case of Pediatric Alliance, with 37 pediatricians in a dozen offices in and around Pittsburgh, the doctors’ group spends at least $250,000 a year on salaries for eight billing clerks who handle claims and pursue money owed by insurers and patients. That is on top of salaries in Pediatric Alliance’s offices for staff members to verify the patient’s coverage and collect co-payments, plus paying an outside company to check for errors before the bills go out.

Ms. Wertz, the alliance’s chief executive, says some insurers’ telephone call centers limit claims-related issues to 10 per call. "That’s incredibly inefficient," she said. "We see thousands of patients. Our people have to sit on phone 30 minutes to get a live person."

. . .

"I would much rather have my staff talking to patients than talking to insurance companies," Dr. Katz said.

For the full story, see:

MILT FREUDENHEIM. "The Check Is Not in the Mail." The New York Times (Thurs., May 25, 2006): C1 & C6.

(Note: The "Dr. Katz" mentioned is "Dr. Molly Katz, a Cincinnati gynecologist and former president of the Ohio Medical Association.")

Charlie Munger. Sourge of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Charlie Munger. Sourge of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.  Alex Tabarrok. Source of image:

Alex Tabarrok. Source of image:

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.