The Flagler Memorial obelisk was erected in on a man-made island in 1920, when Miamians still remembered the accomplishments of Henry Flagler. Source of image: http://www.miamibeachfl.gov/newcity/depts/arce/art_public/rw_flagler_monument.asp

The Flagler Memorial obelisk was erected in on a man-made island in 1920, when Miamians still remembered the accomplishments of Henry Flagler. Source of image: http://www.miamibeachfl.gov/newcity/depts/arce/art_public/rw_flagler_monument.asp

The Standard Oil "monopoly" is often lambasted as a sorry episode in our economic history. And yet a strong case can be made that the Standard Oil wealth was created mainly by efficiently providing consumers with a commodity they valued. In addition, mention is often made of the Rockefeller philanthropic activities. Less known, is that others who became rich from Standard Oil, also engaged in productive entrepreneurship, and philanthropy, with their wealth. One of these was Henry Flagler.

In a region that prizes showy monuments to wealth, the lone monument to the man who made it all possible has languished in isolation for decades.

A soaring concrete obelisk dedicated to Henry Flagler, the oil tycoon who hastened South Florida’s development by building a railroad all the way to Key West, it sits on a tiny man-made island in Biscayne Bay, reachable only by boat or, more typically, Jet Ski. Almost everyone here has glimpsed the Flagler Memorial, but few know what it is called, why it exists or how battered it looks up close.

”I’m telling you, it’s a beautiful work of art,” said Paul Orofino, a board member of the Environmental Coalition of Miami Beach, a nonprofit group that occasionally tidies up Monument Island, the memorial’s scruffy, overgrown home. ”It’s a tragedy that nobody pays attention to this thing.”

It is not the kind of South Florida tribute one might expect for Flagler, who extended his railroad from St. Augustine to West Palm Beach in 1894, Miami in 1896 and Key West — a segment that lasted only 23 years until a hurricane demolished it — in 1912.

Flagler was the state’s original megadeveloper, after all, creating its tourism industry by turning swampy pioneer settlements into the world’s grandest resorts. He was also, perhaps, its first huckster, advertising the nascent Miami as ”the most pleasant place south of Bar Harbor to spend the summer.”

His over-the-top winter home in Palm Beach, awash in gold, is now a museum, but most of its visitors come from out of state, said John Blades, the museum’s executive director. Mr. Blades has tried to get a statue of Flagler erected in Palm Beach, which owes its sumptuous existence to the man, but has so far failed.

”Flagler,” Mr. Blades said, ”is probably the most unappreciated titan of the Gilded Age.”

For the rest of the story of the impressive, but deteriorating, Flagler Memorial in Miami, see:

(Note: the hurricane destroyed the Key West link of the railroad in 1935.)

Henry Flagler. Source of image: http://flaglermuseum.us/html/flagler_biography.html

Henry Flagler. Source of image: http://flaglermuseum.us/html/flagler_biography.html

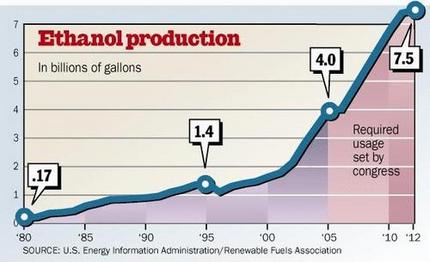

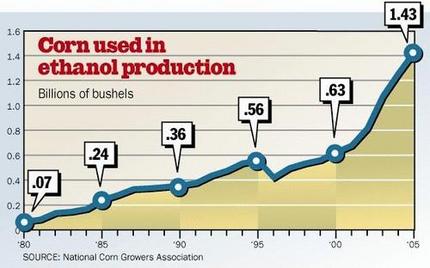

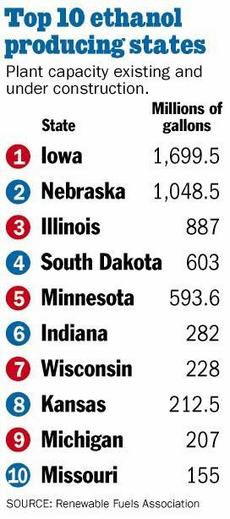

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Cooling towers at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.