(p. 329) . . . those who could stand up to Jobs, including Clow and his teammates Ken Segall and Craig Tanimoto, were able to work with him to create a tone poem that he liked. In its original sixty-second version it read:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

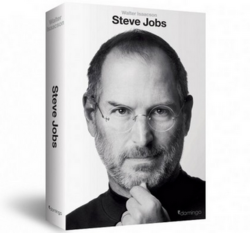

Source:

Isaacson, Walter. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

(Note: ellipsis added.)