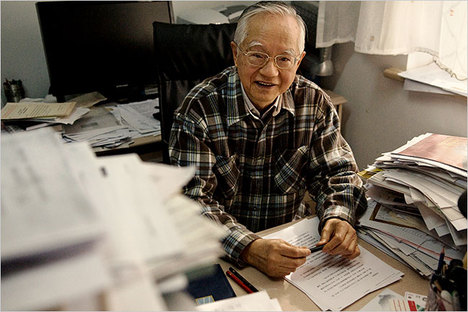

“Josef Janicek, 61, was on the keyboard for a concert in Prague last week by the band Plastic People of the Universe.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Josef Janicek, 61, was on the keyboard for a concert in Prague last week by the band Plastic People of the Universe.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A10) PRAGUE — It has been called the Velvet Revolution, a revolution so velvety that not a single bullet was fired.

But the largely peaceful overthrow of four decades of Communism in Czechoslovakia that kicked off on Nov. 17, 1989, can also be linked decades earlier to a Velvet Underground-inspired rock band called the Plastic People of the Universe. Band members donned satin togas, painted their faces with lurid colors and wrote wild, sometimes angry, incendiary songs.

It was their refusal to cut their long, dank hair; their willingness to brave prison cells rather than alter their darkly subversive lyrics (“peace, peace, peace, just like toilet paper!”); and their talent for tapping into a generation’s collective despair that helped change the future direction of a nation.

“We were unwilling heroes who just wanted to play rock ‘n’ roll,” said Josef Janicek, 61, the band’s doughy-faced keyboard player, who bears a striking resemblance to John Lennon and still sports the grungy look that once helped get him arrested. “The Bolsheviks understood that culture and music has a strong influence on people, and our refusal to compromise drove them insane.”

. . .

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing the band to go underground. In February 1976, the Plastic People organized a music festival in the small town of Bojanovice — dubbed “Magor’s Wedding” — featuring 13 other bands. One month later, the police set out to silence the musical rebels, arresting dozens. Mr. Janicek was jailed for six months; Mr. Jirous and other band members got longer sentences.

Mr. Havel, already a leading dissident, was irate. The trial of the Plastic People that soon followed became a cause célèbre.

Looking back on the Velvet Revolution they helped inspire, however indirectly, Mr. Janicek recalled that on Nov. 17, 1989, the day of mass demonstrations, he was in a pub nursing a beer. He argued that the revolution had been an evolution, fomented by the loosening of Communism’s grip under Mikhail Gorbachev and the overwhelming frustration of ordinary people with their grim, everyday lives. “The Bolsheviks knew the game was up,” he said, “when the sons of the Communists themselves wanted to become capitalists and entrepreneurs.”

For the full story, see:

DAN BILEFSKY. “Czechs’ Velvet Revolution Paved by Plastic People.” The New York Times (Mon., November 16, 2009): A10.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated November 15, 2009.)

(Note: ellipsis added.)