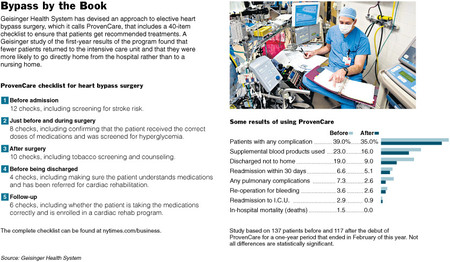

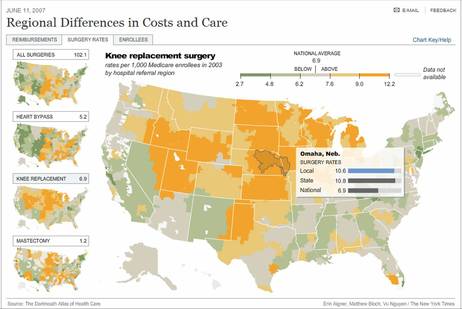

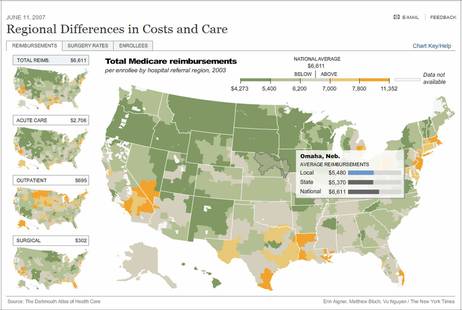

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

(p. A1) An emergency room nurse in Palos Heights, Ill., told Gerard Nussbaum he could not stay with his father-in-law while the elderly man was being treated after a stroke. Another nurse threatened Mr. Nussbaum with arrest for scanning his relative’s medical chart to prove to her that she was about to administer a dangerous second round of sedatives.

The nurses who threatened him with eviction and arrest both made the same claim, Mr. Nussbaum said: that access to his father-in-law and his medical information were prohibited under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or Hipaa, as the federal law is known.

Mr. Nussbaum, a health care and Hipaa consultant, knew better and stood his ground. Nothing in the law prevented his involvement. But the confrontation drove home the way Hipaa is misunderstood by medical professionals, as well as the frustration — and even peril — that comes in its wake.

Government studies released in the last few months show the frustration is widespread, an unintended consequence of the 1996 law.

. . .

(p. A12)

Most common are seat-of-the-pants decisions made by employees who feel safer saying “no” than “yes” in the face of ambiguity.

. . .

Ms. McAndrew said there was no way to know how often information was withheld. Of the 27,778 privacy complaints filed since 2003, the only cases investigated, she said, were complaints filed by patients who were denied access to their own information, the one unambiguous violation of the law.

Complaints not investigated include the plights of adult children looking after their parents from afar. Experts say family members frequently hear, “I can’t tell you that because of Hipaa,” when they call to check on the patient’s condition.

That is what happened to Nancy Banks, who drove from Bartlesville, Okla., to her mother’s bedside at Town and Country Hospital in Tampa, Fla., last week because Ms. Banks could not find out what she needed to know over the telephone.

Her 82-year-old mother had had a stroke. When Ms. Banks called her room she heard her mother “screaming and yelling and crying,” but conversation was impossible. So Ms. Banks tried the nursing station.

Whoever answered the phone was not helpful, so Ms. Banks hit the road. Twenty-two hours later, she arrived at the hospital.

But more of the same awaited her. She said her mother’s nurse told her that “because of the Hipaa laws I can get in trouble if I tell you anything.”

In the morning, she could speak to the doctor, she was told.

The next day, Ms. Banks was finally informed that her mother had had heart failure and that her kidneys were shutting down.

“I understand privacy laws, but this has gone too far,” Ms. Banks said. “I’m her daughter. This isn’t right.”

A hospital spokeswoman, Elena Mesa, was asked if nurses were following Hipaa protocol when they denied adult children information about their parents.

She could not answer the question, Ms. Mesa said, because Hipaa prevented her from such discussions with the press.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

After nurses refused to tell her what was wrong over the phone, Nancy Banks (left) drove 22 hours to find out that her mother Lourene Trusler (right) had had a stroke. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

After nurses refused to tell her what was wrong over the phone, Nancy Banks (left) drove 22 hours to find out that her mother Lourene Trusler (right) had had a stroke. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

In the photo immediately above, Don and Andrea Steirle work in their lab. The map to the left shows the location of the Berkeley Pit. Source of the photo and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Genentech CEO Dr. Arthur D. Levinson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Genentech CEO Dr. Arthur D. Levinson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.