“Marti Conger, a business consultant in Benicia, Calif., went to England in October 2009 to get an implant of a new artificial disk for her spine developed by Spinal Kinetics of Sunnyvale, Calif., a short distance from her home.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Marti Conger, a business consultant in Benicia, Calif., went to England in October 2009 to get an implant of a new artificial disk for her spine developed by Spinal Kinetics of Sunnyvale, Calif., a short distance from her home.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B1) Late last year, Biosensors International, a medical device company, shut down its operation in Southern California, which had once housed 90 people, including the company’s top executives and researchers.

The reason, executives say, was that it would take too long to get its new cardiac stent approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

“It’s available all over the world, including Mexico and Canada, but not in the United States,” said the chief executive, Jeffrey B. Jump, an American who runs the company from Switzerland. “We decided, let’s spend our money in China, Brazil, India, Europe.”

. . .

(p. B7) “Ten years from now, we’ll all get on planes and fly somewhere to get treated,” said Jonathan MacQuitty, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist with Abingworth Management.

Marti Conger, a business consultant in Benicia, Calif., already has. She went to England in October 2009 to get an implant of a new artificial disk for her spine developed by Spinal Kinetics of Sunnyvale, Calif.

“Sunnyvale is 40 miles south of my house,” said Ms. Conger, who has become an advocate for faster device approvals in the United States. “I had to go to England to get my surgery.”

. . .

Device companies have been seeking early approval in Europe for years because it is easier. In Europe, a device must be shown to be safe, while in the United States it must also be shown to be effective in treating a disease or condition. And European approvals are handled by third parties, not a powerful central agency like the F.D.A.

But numerous device executives and venture capitalists said the F.D.A. has tightened regulatory oversight in the last couple of years. Not only does it take longer to get approval but it can take months or years to even begin a clinical trial necessary to gain approval.

Disc Dynamics made seven proposals over three years but could not get clearance from the F.D.A. to conduct a trial of its gel for spine repair, said David Stassen, managing partner of Split Rock Partners, a venture firm that backed the company. “It got to the point where the company just ran out of cash,” Mr. Stassen said. Disc Dynamics was shut down last year after an investment of about $65 million.

For the full story, see:

ANDREW POLLACK. “Medical Treatment, Out of Reach.” The New York Times (Thurs., February 10, 2011): B1 & B7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated February 9, 2011.)

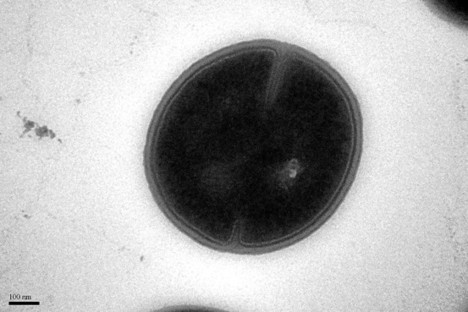

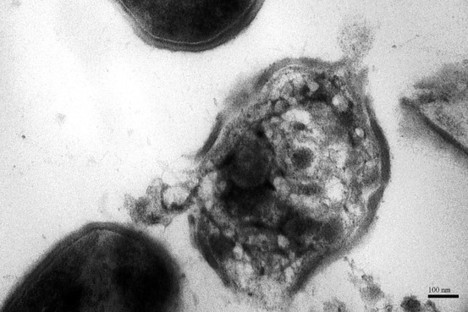

“An artificial disk like the one Marti Conger received.”

Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.