“Government milk is sold mostly through curbside milk stalls. Some customers don’t find the milk stands appealing since they can be dingy and the milk sometimes bad.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. A1) MUMBAI — Every workday morning, milkman D.T. Walkar faithfully comes to Worli Dairy to not deliver milk.

Most days, he and his fellow drivers at the government dairy sign in, then move to the rest area. While others read the paper, nap or play rummy, Mr. Walkar likes to do the Sudoku puzzle in the Maharashtra Times, unless someone else has gotten to it first. He then wanders around the complex and talks to friends. The last delivery trucks were sold last year. “The trucks are all gone so we just sit around and talk,” says Mr. Walkar, 50 years old. “We are bored.”

Once respected civil servants, Mr. Walkar and his 300-odd fellow drivers have been left in a strange limbo. Milk sales at their dairy have plummeted as the state government lost its monopoly on milk and consumer tastes changed. But because Indian work rules strictly protect government workers from layoffs, the delivery men show up for work each morning for eight-hour shifts, as they always did, then proceed to do nothing all day. They rarely, if ever, leave the plant.

. . .

(p. A5) In 2001, the Indian government started opening the dairy market in Maharashtra to competition. Private carriers with higher quality milk swiftly won customers by delivering milk to doorsteps. The government milkmen have always been restricted to delivering mostly to curbside milk stalls so they could cover a greater area.

Customers swiftly deserted. Many switched to heat-treated milk in sealed packages that resist spoiling. Some ditched the government’s former best sellers of sweet Pineapple milk and spicy Masala milk for Coca-Cola and Sprite as Indian tastes westernized. Others never found the milk stands appealing — they can be dingy and the milk sometimes bad.

For the full story, see:

ERIC BELLMAN. “Out to Pasture: India’s Milkmen Bide Their Time; No Work, Secure Job Put Them in Limbo; Where’s the Sudoku?” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., March 29, 2008): A1 & A5.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

“Because Indian work rules protect government workers from layoffs, 300-odd former milk truck drivers show up at the Worli Dairy for work each morning just as they always did, then do nothing all day. To pass the time, the men do puzzles, yoga or just sleep off the hours. Once, they tried planting a garden.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

“Because Indian work rules protect government workers from layoffs, 300-odd former milk truck drivers show up at the Worli Dairy for work each morning just as they always did, then do nothing all day. To pass the time, the men do puzzles, yoga or just sleep off the hours. Once, they tried planting a garden.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

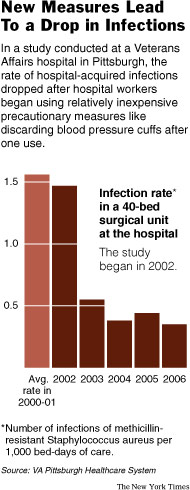

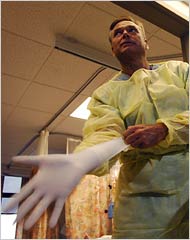

In the photo on the right, Pittsburgh nurse Bill Cunningham, "puts on a gown and gloves before approaching patients with infections." Source of graph, caption, and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

In the photo on the right, Pittsburgh nurse Bill Cunningham, "puts on a gown and gloves before approaching patients with infections." Source of graph, caption, and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.