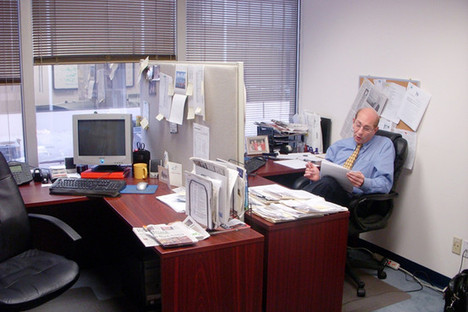

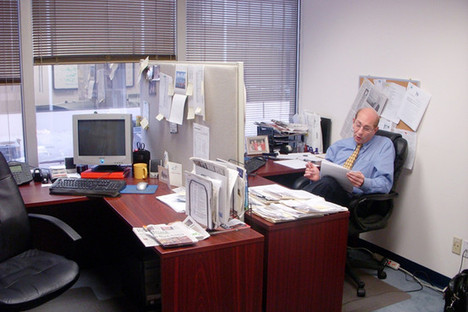

Not Microsoft. “Mark Clemente, a Steinreich Communications vice president, in the firm’s smaller Hackensack, N.J., office.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Not Microsoft. “Mark Clemente, a Steinreich Communications vice president, in the firm’s smaller Hackensack, N.J., office.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

The article quoted below documents the trend in business toward small, and more open offices. I believe that this trend is largely a mistake.

Another trend in business (see Levy and Murnane 2004) is for more jobs to involve thinking and creativity. Thinking and creativity are harder in an environment of noise and frequent and unpredictable interruptions.

David Thielen’s book on the secrets of Microsoft’s success that said that Microsoft emphasized hiring really good people, and then respected them enough to give them an office with a door, so they could have the space and privacy to think and create (e.g., pp. 17-35 & 147-150).

Microsoft had the right idea.

(p. B7) The office cubicle is shrinking, along with workers’ sense of privacy.

Many employers are trimming the space allotted for each worker. The trend has accelerated during the recession as employers seek to cut costs and boost productivity.

. . .

Tighter quarters and open floor plans also can present challenges. David Lewis, president of OperationsInc LLC, a Stamford, Conn., provider of human-resources services to more than 300 U.S. companies, says open floor plans and low cubicle walls can create discord and lead to increased turnover.

“Now everybody knows everybody else’s business,” he says. “It actually starts to create a level of tension in an office that never existed before. People can’t focus on work because they’re on top of each other.”

For the full story, see:

SARAH E. NEEDLEMAN. “THEORY & PRACTICE; Office Personal Space Is Crowded Out; Workstations Become Smaller to Save Costs, Taking a Toll on Employee Privacy.” The Wall Street Journal (Mon., DECEMBER 7, 2009): B7.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The Levy and Murnane book mentioned above, is:

Levy, Frank, and Richard J. Murnane. The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Creating the Next Job Market. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

The Thielen book is:

Thielen, David. The 12 Simple Secrets of Microsoft Management: How to Think and Act Like a Microsoft Manager and Take Your Company to the Top. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999.