"Infosys employs workers in Brno, Czech Republic." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted, and cited, below.

"Infosys employs workers in Brno, Czech Republic." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted, and cited, below.

(p. A1) MYSORE, India — Thousands of Indians report to Infosys Technologies’ campus here to learn the finer points of programming. Lately, though, packs of foreigners have been roaming the manicured lawns, too.

Many of them are recent American college graduates, and some have even turned down job offers from coveted employers like Google. Instead, they accepted a novel assignment from Infosys, the Indian technology giant: fly here for six months of training, then return home to work in the company’s American back offices.

India is outsourcing outsourcing.

One of the constants of the global economy has been companies moving their tasks — and jobs — to India. But rising wages and a stronger currency here, demands for workers who speak languages other than English, and competition from countries looking to emulate India’s success as a back office — including China, Morocco and Mexico — are challenging that model.

Many executives here acknowledge that outsourcing, having rained most heavily on India, will increasingly sprinkle tasks around the globe. Or, as Ashok Vemuri, an Infosys senior vice president, put it, the future of outsourcing is “to take the work from any part of the world and do it in any part of the world.”

. . .

(p. A14) Such is the new outsourcing: A company in the United States pays an Indian vendor 7,000 miles away to supply it with Mexican engineers working 150 miles south of the United States border.

In Europe, too, companies now hire Infosys to manage back offices in their own backyards. When an American manufacturer, for instance, needed a system to handle bills from multiple vendors supplying its factories in different European countries, it turned to the Indian company. The manufacturer’s different locations scan the invoices and send them to an office of Infosys, where each bill is passed to the right language team. The teams verify the orders and send the payment to the suppliers while logged in to the client’s computer system.

More than a dozen languages are spoken at the Infosys office, which is in Brno, Czech Republic.

For the full story, see:

(Note: the somewhat different title of the online version was: "Outsourcing Works So Well, India Is Sending Jobs Abroad.")

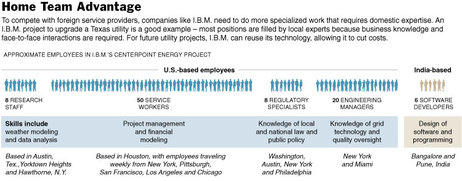

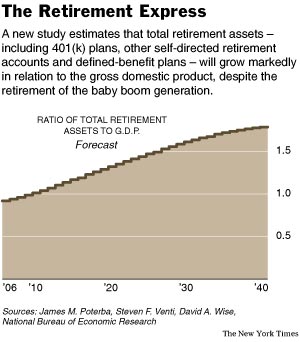

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.