Stephanie and Bill Faunce moved their marketing company from Los Angeles to Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Stephanie and Bill Faunce moved their marketing company from Los Angeles to Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Information technology is making life better by providing greater choice on where to live. There is still a lively debate about which regions and cities will prosper.

One popular take on this issue is Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class.

(p. A1) As technology enables people to live and work wherever they want, increasingly they are clustering in resort playgrounds like Steamboat Springs (pop. 9,315) that have natural amenities, good weather — and, now, lots of people like themselves.

In places like Nantucket, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Teton County, Idaho, the migrants are creating hybrid communities, implanting urban incomes, tastes, careers, ambitions, restaurants, cultural activities and networking opportunities into small towns that un-(p. A15)til recently could support none of these, and for which there has been little planning and still no consensus.

“You are seeing a transformation of rural communities,” said Jonathan Schechter, executive director of the Charture Institute in Jackson, Wyo., a nonprofit organization that studies small recreational towns.

Into quiet resort spots the migrants have come, laptops on their knees: fund managers from New York, software developers from California, consultants, proofreaders, engineers, inventors. “The same processes that led to the suburbanization of the United States after World War II,” Mr. Schechter said, “are now producing a virtual suburbanization in places like Jackson or Steamboat Springs.”

From 2000 to 2006, population in the 297 counties rated highest in natural amenities by the United States Department of Agriculture grew by 7.1 percent, 10 times the rate for the 1,090 rural counties with below-average amenities, the department reported.

In towns that once emptied after the ski season or the beach season, these “location-neutral” migrants are complicating the traditional dynamic between tourists and locals. Here as elsewhere, average homes have become unaffordable for teachers, firefighters and others — the people who created the good schools and community closeness that newcomers said drew them. The rate of change “is causing a whiplash,” Mr. Schechter said, “because the towns don’t have the political and economic systems in place to deal with them.”

Routt County, which includes Steamboat Springs, is one of the first places to identify these new émigrés as a source of economic growth and, paradoxically, community stability. A 2005 survey found that as many as 1 in 10 year-round households was involved in a location-neutral business. Unlike retirees and second-home buyers, who are also roosting in vacation towns, they send children to the local schools. “Without kids, you don’t have a community,” said Scott Ford, a counselor at the Small Business Resource Center at Colorado Mountain College.

Cloistered in home offices, isolated from the local economy, location-neutrals are often invisible even to one another, except when they appear on local committees.

Many work as hard as their urban counterparts, often juggling commitments in several time zones, but can step from their offices to a hiking trail or mountain stream.

. . .

For Bill and Stephanie Faunce, who run a marketing company for cable operators, small-town life often means starting work at 7 a.m. and quitting at 11 p.m., but with breaks to hike, ski or be with their two young children. Their goal in coming here was not to slow down but to eliminate urban distractions and pressures.

“There are no stressors here,” said Mr. Faunce, 43. “In L.A., it took 90 minutes to get to the office, so we had a Mercedes and a Land Rover. Now we drive a Suburban. In three years we’ve put 15,000 miles on it.”

For the full story, see:

JOHN LELAND. "Off to Resorts, and Carrying Their Careers." The New York Times (Mon., August 13, 2007): A1 & A15.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The reference for Florida’s book, is:

Florida, Richard. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

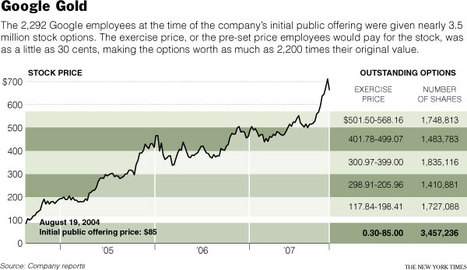

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

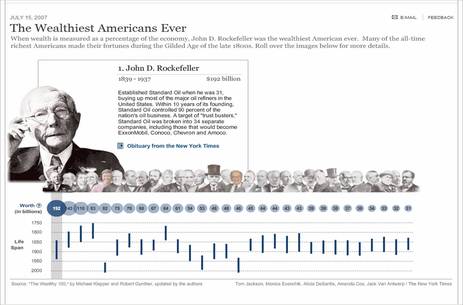

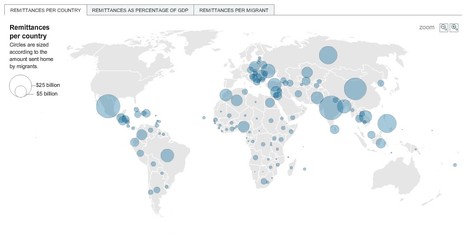

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

"The bolt hole was designed to hide from angry textile workers." Source of caption and photo: the BBC article quoted and cited below, and viewable at

"The bolt hole was designed to hide from angry textile workers." Source of caption and photo: the BBC article quoted and cited below, and viewable at

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.