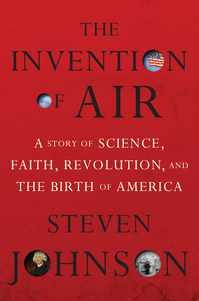

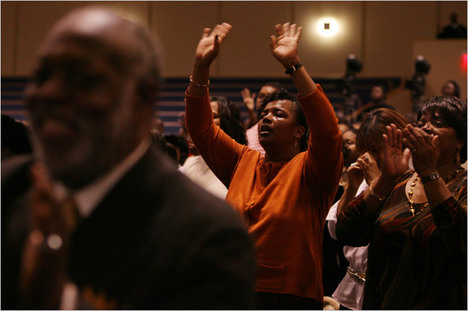

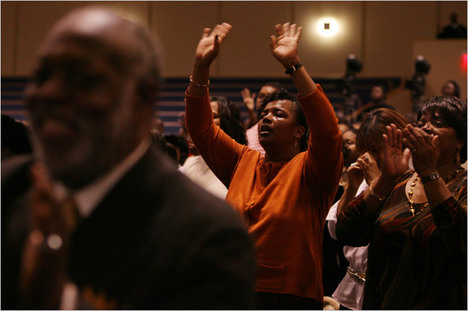

“PRAYING FOR A MIRACLE. S.U.V.’s sat on the altar of Greater Grace Temple, a Pentecostal church in Detroit, as congregants prayed to save the auto industry.” Source of the caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“PRAYING FOR A MIRACLE. S.U.V.’s sat on the altar of Greater Grace Temple, a Pentecostal church in Detroit, as congregants prayed to save the auto industry.” Source of the caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

The process of creative destruction, requires that failed businesses be allowed to fail, so that the resources (labor and capital) devoted to the failed businesses, can be devoted to more productive uses.

The Danny DeVito character in “Other People’s Money” makes this point in a speech near the end, in which he says that the Gregory Peck character has just delivered a “prayer for the dead” in calling for continued support for a dead business that is technologically obsolete.

On a more personal level, we have always bought cars from Honda and Toyota, because we sincerely believe that they build better cars than Detroit does. By what right does the government force taxpayers to prop up companies whose products have been rejected in the marketplace?

When the economic and moral arguments for bailout fail, all that is left for a failed industry is prayer (and politics)—one more reason to believe that the opportunity cost of prayer, is high.

(p. A19) DETROIT — The Sunday service at Greater Grace Temple began with the Clark Sisters song “I’m Looking for a Miracle” and included a reading of this verse from the Book of Romans: “I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us.”

Pentecostal Bishop Charles H. Ellis III, who shared the sanctuary’s wide altar with three gleaming sport utility vehicles, closed his sermon by leading the choir and congregants in a boisterous rendition of the gospel singer Myrna Summers’s “We’re Gonna Make It” as hundreds of worshipers who work in the automotive industry — union assemblers, executives, car salesmen — gathered six deep around the altar to have their foreheads anointed with consecrated oil.

While Congress debated aid to the foundering Detroit automakers Sunday, many here whose future hinges on the decision turned to prayer.

Outside the Corpus Christi Catholic Church, a sign beckoned passers-by inside to hear about “God’s bailout plan.”

For the full story, see:

NICK BUNKLEY. “Detroit Churches Pray for ‘God’s Bailout’.” The New York Times (Mon., December 8, 2008): A19.

(Note: The photo of the top appeared on p. A1 of the print edition of the December 8, 2008 NYT; also, the online version of the article has a date of Dec. 7 instead of the Dec. 8 date of the print version.)

“Worshipers at Greater Grace Temple, a Pentecostal church in Detroit, prayed on Sunday for an automobile industry miracle.” Source of the caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Worshipers at Greater Grace Temple, a Pentecostal church in Detroit, prayed on Sunday for an automobile industry miracle.” Source of the caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.