Decades ago, I really enjoyed the spirit, and sometimes the usefulness, of Stewart Brand’s refreshing, libertarian, over-the-top Whole Earth Catalog. From the article excerpted below, I learned that Brand, and his spirit, are still alive:

(p. D1) Stewart Brand has become a heretic to environmentalism, a movement he helped found, but he doesn’t plan to be isolated for long. He expects that environmentalists will soon share his affection for nuclear power. They’ll lose their fear of population growth and start appreciating sprawling megacities. They’ll stop worrying about “frankenfoods” and embrace genetic engineering.

He predicts that all this will happen in the next decade, which sounds rather improbable — or at least it would if anyone else had made the prediction. But when it comes to anticipating the zeitgeist, never underestimate Stewart Brand.

He divides environmentalists into romantics and scientists, the two cultures he’s been straddling and blending since the 1960s. He was with the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead at their famous Trips Festival in San Francisco, directing a multimedia show called “America Needs Indians.” That’s somewhere in the neighborhood of romantic.

But he created the shows drawing on the cybernetic theories of Norbert Wiener, the M.I.T. mathematician who applied principles of machines and electrical networks to social institutions. Mr. Brand imagined replacing the old technocratic hierarchies with horizontal information networks — a scientific vision that seemed quaintly abstract until the Internet came along.

. . .

(p. D3) Mr. Brand’s latest project, undertaken with fellow digerati, is to build the world’s slowest computer, a giant clock designed to run for 10,000 years inside a mountain in the Nevada desert, powered by changes in temperature. The clock is an effort to promote long-term thinking — what Mr. Brand calls the Long Now, a term he borrowed from the musician Brian Eno.

Mr. Brand is the first to admit his own futurism isn’t always prescient. In 1969, he was so worried by population growth that he organized the Hunger Show, a weeklong fast in a parking lot to dramatize the coming global famine predicted by Paul Ehrlich, one of his mentors at Stanford.

The famine never arrived, and Professor Ehrlich’s theories of the coming “age of scarcity” were subsequently challenged by the economist Julian Simon, who bet Mr. Ehrlich that the prices of natural resources would fall during the 1980s despite the growth in population. The prices fell, just as predicted by Professor Simon’s cornucopian theories.

Professor Ehrlich dismissed Professor Simon’s victory as a fluke, but Mr. Brand saw something his mentor didn’t. He considered the bet a useful lesson about the adaptability of humans — and the dangers of apocalyptic thinking.

“It is one of the great revelatory bets,” he now says. “Any time that people are forced to acknowledge publicly that they’re wrong, it’s really good for the commonweal. I love to be busted for apocalyptic proclamations that turned out to be 180 degrees wrong. In 1973 I thought the energy crisis was so intolerable that we’d have police on the streets by Christmas. The times I’ve been wrong is when I assume there’s a brittleness in a complex system that turns out to be way more resilient than I thought.”

He now looks at the rapidly growing megacities of the third world not as a crisis but as good news: as villagers move to town, they find new opportunities and leave behind farms that can revert to forests and nature preserves. Instead of worrying about population growth, he’s afraid birth rates are declining too quickly, leaving future societies with a shortage of young people.

Old-fashioned rural simplicity still has great appeal for romantic environmentalists. But when the romantics who disdain frankenfoods choose locally grown heirloom plants and livestock, they’re benefiting from technological advances made by past plant and animal breeders. Are the risks of genetically engineered breeds of wheat or cloned animals so great, or do they just ruin the romance?

Mr. Brand would rather take a few risks.

“I get bored easily — on purpose,” he said, recalling advice from the co-discoverer of DNA’s double helix. “Jim Watson said he looks for young scientists with low thresholds of boredom, because otherwise you get researchers who just keep on gilding their own lilies. You have to keep on trying new things.”

That’s a good strategy, whether you’re trying to build a sustainable career or a sustainable civilization. Ultimately, there’s no safety in clinging to a romanticized past or trying to plan a risk-free future. You have to keep looking for better tools and learning from mistakes. You have to keep on hacking.

Source of book image: http://ec1.images-amazon.com/images/P/1586483501.01._SS500_SCLZZZZZZZ_.jpg

Source of book image: http://ec1.images-amazon.com/images/P/1586483501.01._SS500_SCLZZZZZZZ_.jpg

Two views of the new parking meters in Redwood, California. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Two views of the new parking meters in Redwood, California. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Sensors such as the one embedded in the San Francisco street on the left, could eventually be used to help track parking violators, as imagined in the fictional picture on the right. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Sensors such as the one embedded in the San Francisco street on the left, could eventually be used to help track parking violators, as imagined in the fictional picture on the right. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

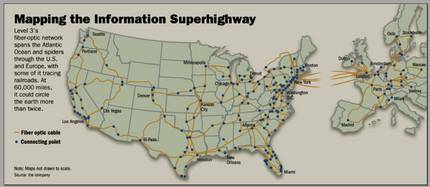

Level 3 stock prices. Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Level 3 stock prices. Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.