David Sinclair (left) and Christoph Westphal (right). Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

David Sinclair (left) and Christoph Westphal (right). Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Humans are often risk-averse, but are also often willing to accept greater risk, in the pursuit of a really important goal.

SIRTRIS PHARMACEUTICALS wants to sell you the elixir of youth. Yet the company’s founders are neither cranks nor quacks, but include a well-regarded Harvard scientist and a serial entrepreneur.

Imagine a pill, derived from a compound found in something as benign as red wine, that treated the most feared and debilitating diseases of aging: illnesses like diabetes, neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and many forms of cancer. Imagine, furthermore, that this pill had no injurious side effects. Imagine, finally, that the pill’s only side effect conferred what human beings have always wanted: an increase in life span. That’s what Sirtris wants to create.

. . .

Mr. Sinclair, who at the relatively youthful age of 37 is already renowned for his investigations into how we grow old, discovered in 2003 that a molecular compound called resveratrol, found in red wine and other plant products, extends the life span of mice by as much as 24 percent and the life span of other animals, such as flies and fish, by as much as 59 percent.

Dr. Westphal, a self-described “geek” who relaxes by reading papers in academic journals like Nature and Science, was stunned by Mr. Sinclair’s discovery, and visited him in his lab to discuss the implications for drug development. The two soon decided to start a company.

“I figured if there’s going to be one chance that I’d take an 80 percent pay cut to be the C.E.O. of a company rather than general partner in a venture firm, then this was it,” Dr. Westphal, 39, told me when I visited Sirtris’s offices in Cambridge, Mass. “If we’re right on this one, everyone’s going to want to take these drugs and they’re going to treat many of the major diseases of Western society.”

. . .

“Nobody knows why we age,” Mr. Sinclair explained to me. “We’re working on genes that increase fitness and defenses against diseases. The body mounts those defenses when it’s under adversity. Caloric restriction is one of those triggers and the molecules we’re developing are also one of those triggers.”

Dr. Westphal and Mr. Sinclair stress that they are not working to “cure” aging, a condition that, so far at least, is common to all humanity and that most physicians do not consider a disease. “Curing aging is not an endpoint the federal drug agency would recognize,” Dr. Westphal says dryly. Instead, both men say, they are working to ameliorate the diseases of aging.

While Mr. Sinclair has bragged that resveratrol is as “close to a miraculous molecule as you get,” much uncertainty surrounds his research and the commercialization of his discovery faces many challenges.

. . .

Sirtris hopes to have its first drugs in commercial production by 2012 or 2013. While that may seem far off, it’s wonderfully fast for the biopharmaceutical industry, where development is onerously slow, difficult and uncertain.

This speed of research and development owes much to Dr. Westphal’s energy and Mr. Sinclair’s ambition.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to develop drugs that combat diseases of aging,” Mr. Sinclair says. “As soon as I realized I was mortal, I started to worry. I set a goal to see if we could make drugs that would target the diseases of aging in my lifetime. I didn’t know it would be possible at all — and I didn’t know it would happen so quickly.”

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

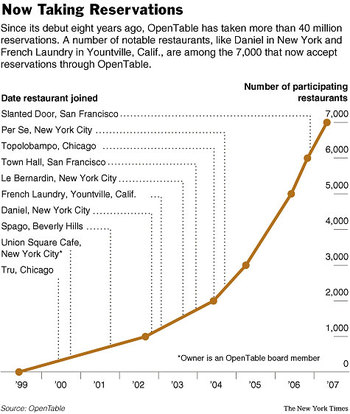

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

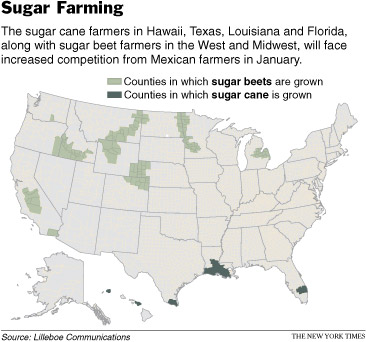

Source of graphic: online version of NYT article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of NYT article cited above.

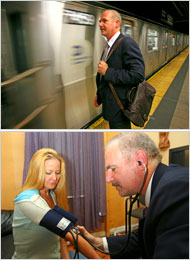

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above. Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.