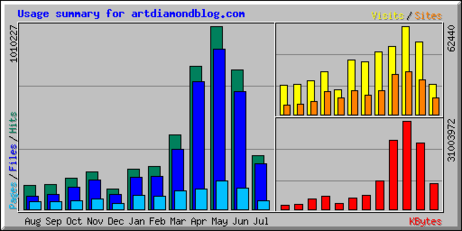

The bars for "July" only include data through July 13th. Although the best-known metric is "hits" (in green), a more meaningful metric, for many purposes, is "visits" (in yellow). The source of this graph is the Webalizer program as maintained by the Living Dot service that houses my blog. (The graph above was produced in the evening of July 14, 2007.)

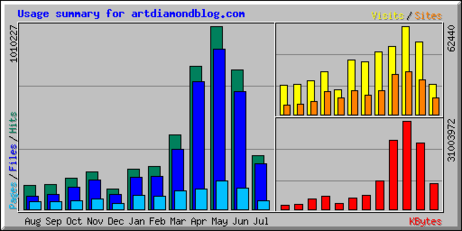

The bars for "July" only include data through July 13th. Although the best-known metric is "hits" (in green), a more meaningful metric, for many purposes, is "visits" (in yellow). The source of this graph is the Webalizer program as maintained by the Living Dot service that houses my blog. (The graph above was produced in the evening of July 14, 2007.)

The first entry in artdiamondblog.com appeared on July 15, 2005. In the two years since, the blog remains true to its modest and vague founding motives, but has evolved in some small ways. I think pictures and graphs help communicate many important stories, and make them more memorable. So the blog in recent months generally includes such elements in about half the entries. Even better are dynamic accounts of stories, so I have gradually increased the links to video clips that illustrate important stories.

Also, more often than at the beginning, I offer my own somewhat extended commentary on some person, issue, event, book or article. As time permits, I have also tried to include an occasional entry that records some reminiscence of some important scholar or telling experience that I have had, that I hope might be of value to someone in the future. (One example of this sort of entry, in the past year, was my entry on Milton Friedman on the occasion of his death.)

I believe that the web log is useful in my teaching and research, and also hope that it provides easier access to some useful material for others who share my interests and goals.

Of course, every activity has its opportunity costs. I try to limit the costs by disciplining myself to only post one new entry a day. And I try to take advantage of blogging economies of scale, by composing several entries at a time, and pre-scheduling them into the future.

The benefits are hard to access. I know that in June (the most recent full month for which data is available), the average daily number of "visits" to my blog was recorded as 1,132. But I do not know very much about how useful the visitors found the blog, or if useful, how often the use is the kind of use I originally had in mind.

On the other hand, I believe that the process writing and publishing refereed journal articles has its drawbacks. It is slow, and the refereeing is uneven, and often actually makes an article worse. When the article is finally published, it is often in a form easily accessible only to a few, and as a result often has negligible impact on knowledge or on the broader world of action.

So I think it is time to take some risks with some experimentation in other forms of knowledge production and communication. Wikipedia is one promising experiment. Blogs represent another.

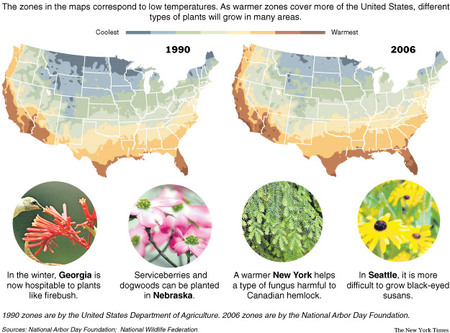

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"The victim, Kathryn Johnson, was described as either 88 or 92." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

"The victim, Kathryn Johnson, was described as either 88 or 92." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

"A truck driver makes his way through snow-covered trucks Tuesday in Punta de Vacas, Argentina." Source of the truck caption and photo:

"A truck driver makes his way through snow-covered trucks Tuesday in Punta de Vacas, Argentina." Source of the truck caption and photo:  Al Gore dreams of Rachel Carson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Al Gore dreams of Rachel Carson. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Dubai skyline. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ commentary quoted and cited below.

Dubai skyline. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ commentary quoted and cited below.