Much has been made of the good will between the Bushes and the late Enron CEO Ken Lay. But not all of those who fall short of sainthood are friends of Republicans. During the Clinton administration, Vinod Gupta slept at the White House. He is a major donor to Democrats, and has been a delegate to the Democratic National Convention. Yet Gretchen Morgenson of the New York Times suggests that Gupta may not be an exemplar of sound management practices:

(p. 1) ANYONE who says that the Midwest is dull and monochromatic has obviously never been to Omaha. The city of Warren E. Buffett, the investing great who has generated huge gains for his shareholders over the years, is also home to Vinod Gupta, the colorful chief executive of infoUSA, who has destroyed enormous value for outside shareholders in recent years. Now that’s diversity.

Unfortunately for the shareholders of infoUSA, a database marketing concern, much of its story is a throwback to the pre-Enron days of cozy boards and entitled executives. Mr. Gupta, who founded infoUSA in 1972 and owns 38 percent of its shares, doesn’t seem to recognize that he is running a public company and needs to look out for his non-Gupta shareholders. His board has done little to help him see the light.

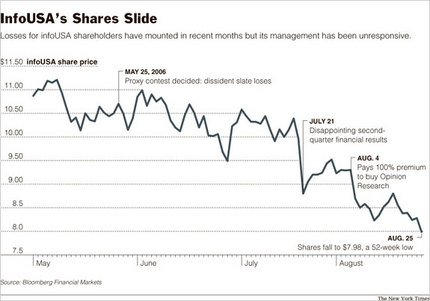

InfoUSA shares hit a 52-week low Friday, closing at $7.98. They are down 27 percent for the period.

Mr. Gupta is, shall we say, a piece of work. He often prevents large shareholders from asking questions on conference calls. He has received compensation that was not earned under the terms of the company’s executive compensation program, according to a lawsuit that Cardinal Value Equity Partners, infoUSA’s largest outside holder, filed against the company. And, the suit alleges, his board has given him free rein to dispense stock options to whomever he likes.

Related-party transactions are also routine at infoUSA. The Cardinal lawsuit contends that infoUSA paid a company owned by Mr. Gupta about $608,000 in 2003 to buy his interest in a skybox at the University of Nebraska’s Memorial Stadium. The university is Mr. Gupta’s alma mater and home of the Cornhuskers football team. In June 2005, the suit says, infoUSA paid $2.2 million for a long-term lease of his yacht. The yacht, named American Princess, is 80 feet long and has an all-female crew, according to a report in The Triton, a monthly publication for boat captains and crews.

Leases on an H2 Hummer, a gold Honda Odys-(p. 8)sey, a Glacier Bay Catamaran, a Mini Cooper, a Lexus 330, a Mercedes SL500 — all used by the Gupta clan — as well as rent on a Gupta family condominium on Maui have also been financed by infoUSA shareholders, the suit said.

Shareholders also paid a company owned by Mr. Gupta’s wife $64,200 for consulting services in 2003 and 2004. Shareholders have also covered the Gupta family’s personal use of a corporate jet — leased by infoUSA from a company owned by the family — to have fun in the sun in Hawaii and the Bahamas. Mr. Gupta apparently wasn’t in a mood to return the favor: during a four-year period ending in 2004, infoUSA paid $13.5 million to Mr. Gupta’s private company for use of the aircraft.

What to make of all of this? The Cardinal lawsuit contends that the carnivalesque spending amounts to unregulated perquisites and evidence of a somnambulant board. Sleepy, perhaps, but always on the move. Some 15 directors have spun through infoUSA’s boardroom door over the last decade; five of them stayed less than a year.

For the full story, see:

Gretchen Morgenson. "That Other Guy From Omaha." The New York Times, Section 3 (Sun., August 27, 2006): 1 & 8.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

“Visitors to the Palestinian Contemporary Art Museum in Tehran Thursday viewed entries in a contest for cartoons ridiculing the Holocaust.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

“Visitors to the Palestinian Contemporary Art Museum in Tehran Thursday viewed entries in a contest for cartoons ridiculing the Holocaust.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

A cul-de-sac in Eagan, Minnesota. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

A cul-de-sac in Eagan, Minnesota. Source of photo: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ editorial cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ editorial cited below.

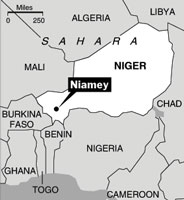

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Michelle Bachelet. Souce of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Michelle Bachelet. Souce of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.