Left photo shows Dennis Okelo in the grocery store that he opened with savings from growing cotton, and selling it to Dunavant. Right photo shows a Dunavant cotton gin in Zambia. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Left photo shows Dennis Okelo in the grocery store that he opened with savings from growing cotton, and selling it to Dunavant. Right photo shows a Dunavant cotton gin in Zambia. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

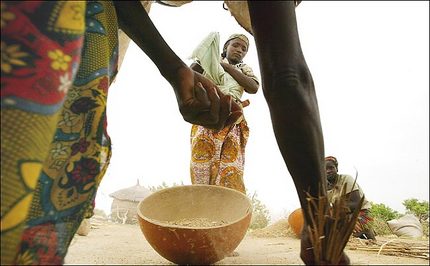

(p. 1) WHERE is he?” the old woman asks. “Where is he?”

Finding Dennis Okelo used to be easy. The old woman — and most other people in a village outside of Lira, the provincial capital of northern Uganda — went directly to Mr. Okelo’s fields. He was always in one of his “gardens,” with his slacks rolled up above his calves and a short hoe close by. Or he was seated outside of his mud-brick house under a banana tree.

Then cotton growing revived in Uganda, and Dunavant Enterprises came to town about five years ago, paying cash on delivery. After three seasons of growing cotton for Dunavant, the world’s largest privately owned cotton broker and one of the biggest family-owned agribusinesses in the United States, Mr. Okelo, who owns less than three acres and has two wives and a passel of children, had saved $300, about double his annual earnings before Dunavant started buying his cotton.

Last summer, Mr. Okelo opened a grocery store, which is where the old woman finally found him: smiling, standing behind the wooden plank that serves as his service counter in a shop the size of a utility shed. The grocery, one of two in the village, carries dried foods, cooking oil, matches, cosmetics, batteries and candy.

“Before Dunavant, no one came to help us,” says Mr. Okelo, 40, who has farmed a variety of crops in these parts for about 20 years.

. . .

(p. 7) IN his small shop, Mr. Okelo knows nothing of global developments in the cotton trade even though he is a direct beneficiary of them. He started farming during the lean years in Uganda, after the ouster of the country’s notorious dictator, Idi Amin, when the cultivation of cotton lagged so badly that production nearly ceased and farmers treated the crop like a weed.

A few years ago, as Uganda’s production began to revive, Dunavant’s trainers taught Mr. Okelo to grow cotton in straight rows and to use a string to measure precisely the distance between rows, to maximize plantings. Mr. Okelo’s new methods are basic, but in a part of Africa where farmers work the land chiefly with a hoe — and tractors, fertilizer and pesticides are rarities — even basic improvements can lead to large gains in production.

“Cotton is the crop that gives farmers the best money,” Mr. Okelo said. “I want Dunavant to be even closer to me.”

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

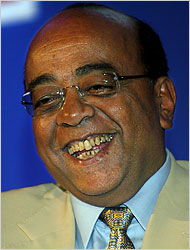

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

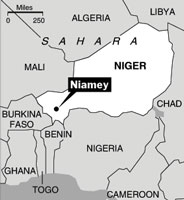

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.  Nicholas D. Kristof. Source of image: online verison of the NYT commentary cited below.

Nicholas D. Kristof. Source of image: online verison of the NYT commentary cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.