JACQUELINE NOVOGRATZ, a veteran of the Rockefeller Foundation and a former consultant to the World Bank, talks enthusiastically about the development of a company in Africa where some 2,000 women earn, on average, $1.80 a day producing antimalarial bed netting. With the assistance of a $350,000 loan from an American investor, the business started making the nets nearly three years ago and is likely to add 1,000 more jobs within the next year.

”They’re in the process of building a real company town there,” Ms. Novogratz said.

Ms. Novogratz is not an outsourcing executive at a multinational company. Rather, she is the chief executive of the Acumen Fund, a philanthropic start-up based in New York that uses donations to make equity investments and loans in both for-profit and nonprofit companies in impoverished countries. One of the stars of her small portfolio is the bed-netting maker, A to Z Manufacturing, a family-owned company in Tanzania — a country where 80 percent of the population makes less than $2 a day.

. . .

”To put it in the baldest possible terms, the more sweatshops the better,” said William Easterly, professor of economics at New York University and author of ”The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good.” Professor Easterly is not advocating the deliberate creation of workplaces with miserable conditions. ”As you increase the number of factories demanding labor, wages will be driven up,” he said, and eventually such factories will not be sweatshops.

Ms. Novogratz says it can be difficult to tell well-off, philanthropy-minded Westerners that what Africa really needs is more $2-a-day jobs. But when they understand the alternatives, she said, such concerns tend to melt away. Before they found work at the netting factory in Tanzania, for example, many of the women were street vendors or domestic workers and earned less than $1 a day. A to Z’s wages place the women in Tanzania’s top quartile of earners, Ms. Novogratz said.

For the full commentary, see:

Source of book image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Source of book image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

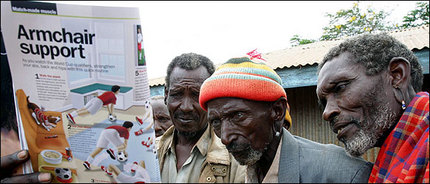

Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.