“Shi Kang, a millionaire writer living in Beijing, started thinking about emigrating after a long road trip last year around the U.S.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

“Shi Kang, a millionaire writer living in Beijing, started thinking about emigrating after a long road trip last year around the U.S.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. A1) BEIJING–This time last year, Shi Kang considered himself a happy man.

Writing 15 novels had made him a millionaire. He owned a luxury apartment and a new silver Mercedes. He was so content with his carefree life in Beijing that he never even traveled overseas.

Today, a year later, Mr. Shi is considering emigrating to the U.S.–one of a growing number of rich Chinese either contemplating leaving their homeland or already arranging to do it.

. . .

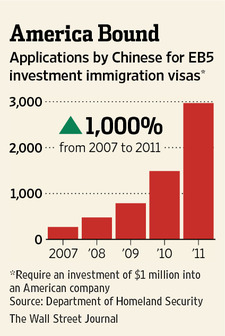

(p. A12) A survey published in November found that 60% of about 960,000 Chinese people with assets over 10 million yuan ($1.6 million) were either thinking about emigrating or taking steps to do so. The U.S. was the top destination, followed by Canada, Singapore and Europe, according to the survey by the state-run Bank of China and Hurun Report, which analyzes trends among China’s wealthy.

. . .

Mr. Su was no dissident, though. Like many of his generation, he turned his attention to getting rich. Today, at 46, Mr. Su runs his own aerospace technology company and estimates his own net worth, including the various properties he owns, at around 80 million yuan, or close to $13 million.

His main reason for leaving, he says, is the business environment. “The government has too much power,” he says. “Regulations here mean that businessmen have to do a lot of illegal things. That gives people a real sense of insecurity.” He said four of his distributors have also applied for investment immigration to Canada.

. . .

“The problem is that government power is too great,” Mr. Su says. “When the economy is going up, they think that everything they are doing is right.” If they don’t change, he worries, “another revolution will come soon.”

. . .

The current migrant wave is different in that they are escaping neither poverty nor political unrest–and many say they are leaving for good. The Hurun survey showed that the average respondent had 60 million yuan in assets and was 42, old enough to remember the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, but young enough to have learned how to prosper in a market economy.

Deng Jie fits the profile. Twenty-seven years ago, in the fledgling years of China’s market reforms, he began his career in a state-run ceramics factory in Beijing, sharing a cramped dormitory with colleagues and earning 50 yuan a month (about $13 in those days).

Today, at 48, he runs his own chemical pigments business and lives with his wife and daughter in one of the three luxury apartments he owns. In dollar terms, he is a millionaire several times over. His properties alone have appreciated by 800% in a decade.

Yet the hope he felt for his country in the 1980s, he says, has “been doused with bucket after bucket of cold water.” He cited a host of concerns, including rampant corruption among the officials he deals with, and new labor regulations that he says have made his work force too costly and demanding.

“I’m representing a lot of other people like me,” he says. “We used to want to contribute to the nation. But now we just feel so disappointed. China cannot continue like this. It has to change.”

For the full story, see:

JEREMY PAGE. “Plan B for China’s Wealthy: Moving to the U.S., Europe.” The Wall Street Journal (Thurs., FEBRUARY 22, 2012): A1 & A12.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.