“As China’s roaring economy fuels a wild construction boom around the country, critics cite places like Kangbashi as proof of a speculative real estate bubble they warn will eventually burst.” Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of caption: online version of the NYT slideshow that accompanied the online article quoted and cited below.

“As China’s roaring economy fuels a wild construction boom around the country, critics cite places like Kangbashi as proof of a speculative real estate bubble they warn will eventually burst.” Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of caption: online version of the NYT slideshow that accompanied the online article quoted and cited below.

The October 19, 2010 New York Times front page story (quoted below) on the Ordos ghost town in China, was finally picked up by the TV media on May 30 in a nice NBC Today Show report.

It should be clear that the Chinese real estate bubble will burst, just as real estate bubbles eventually burst in places like Japan and the United States. What is not clear is what the effects will be on the Chinese and world economies.

(p. A1) Ordos proper has 1.5 million residents. But the tomorrowland version of Ordos — built from scratch on a huge plot of empty land 15 miles south of the old city — is all but deserted.

Broad boulevards are unimpeded by traffic in the new district, called Kangbashi New Area. Office buildings stand vacant. Pedestrians are in short supply. And weeds are beginning to sprout up in luxury villa developments that are devoid of residents.

. . .

(p. A4) As China’s roaring economy fuels a wild construction boom around the country, critics cite places like Kangbashi as proof of a speculative real estate bubble they warn will eventually pop — sending shock waves through the banking system of a country that for the last two years has been the prime engine of global growth.

. . .

Analysts estimate there could be as many as a dozen other Chinese cities just like Ordos, with sprawling ghost town annexes. In the southern city of Kunming, for example, a nearly 40-square-mile area called Chenggong has raised alarms because of similarly deserted roads, high-rises and government offices. And in Tianjin, in the northeast, the city spent lavishly on a huge district festooned with golf courses, hot springs and thousands of villas that are still empty five years after completion.

. . .

In 2004, with Ordos tax coffers bulging with coal money, city officials drew up a bold expansion plan to create Kangbashi, a 30-minute drive south of the old city center on land adjacent to one of the region’s few reservoirs. . . .

In the ensuing building spree, home buyers could not get enough of Kangbashi and its residential developments with names like Exquisite Silk Village, Kanghe Elysees and Imperial Academic Gardens.

Some buyers were like Zhang Ting, a 26-year-old entrepreneur who is a rare actual resident of Kangbashi, having moved to Ordos this year on an entrepreneurial impulse.

“I bought two places in Kangbashi, one for my own use and one as an investment,” said Mr. Zhang, who paid about $125,000 for his 2,000-square-foot investment apartment. “I bought it because housing prices will definitely go up in such a new town. There is no reason to doubt it. The government has already moved in.”

Asked whether he worried about the lack of other residents, Mr. Zhang shrugged off the question.

“I know people say it’s an empty city, but I don’t find any inconveniences living by myself,” said Mr. Zhang, who borrowed to finance his purchases. . . .

For the full story, see:

DAVID BARBOZA. “A City Born of China’s Boom, Still Unpeopled.” The New York Times (Weds., October 19, 2010): A1 & A4.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary is dated October 19, 2010 and has the title “Chinese City Has Many Buildings, but Few People.”)

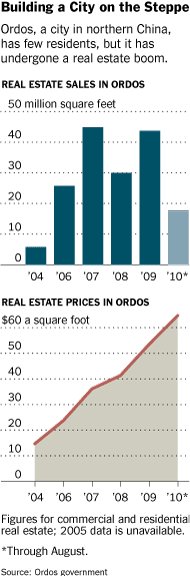

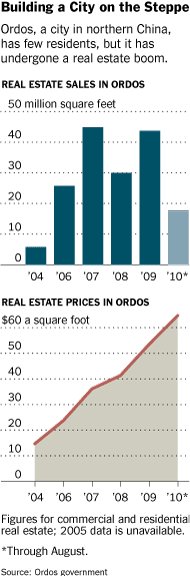

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.