Clayton Christensen has shown how good management, following respected practices, can fail in the face of disruptive technologies. It would be interesting to investigate whether Fairchild was an example of what Christensen is talking about, or whether it just did not have good management.

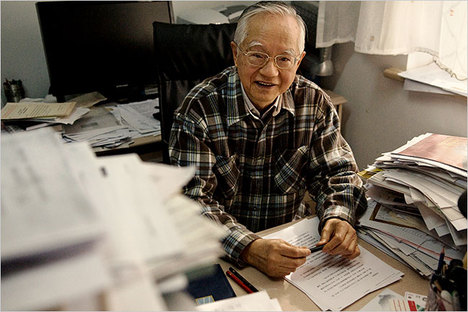

(p. 89) Andrew Grove . . . had played a central role in bringing Fairchild to the threshold of a new era. But Fairchild would not enjoy the fruits of his work. Following the path of venture capital pioneer Peter Sprague were scores of other venture capitalists seeking to exploit the new opportunities he had shown them. Collectively, they accelerated the pace of entrepreneurial change–splits and spinoffs, startups and staff shifts–to a level that might be termed California Business Time (“What do you mean, I left Motorola quickly?” asked Gordon Campbell with sincere indignation. “I was there eight months!”).

The venture capitalist focused on Fairchild: that extraordinary pool of electronic talent assembled by Noyce and Moore, but left essentially unattended, undervalued, and little understood by the executives of the company back in Syosset, New York. Fairchild leaders John Carter and Sherman Fairchild commanded the microcosm: the most important technology in the history of the human race. Noyce, Moore, Hoerni, Grove, Sporck, design genius Robert Widlar, and marketeer Jerry Sanders represented possibly the most potent management and technical team ever assembled in the history of world business. But, hey, you guys, don’t forget to report back to Syosset. Don’t forget who’s boss. Don’t give out any bonuses without clearing them through the folks at Camera and Instrument. You might upset some light-meter manager in Philadelphia.

They even made Charles Sporck, the manufacturing titan, feel like “a little kid pissing in his pants.” Good work, Sherman, don’t let the big lug put on airs, don’t let him feel important. He only controls 80 percent of the company’s growth. Widlar is leaving? Great, he never fit in with the corporate culture anyway. Sporck has gone off with Peter Sprague? There are plenty more where he came from.

“It was weird,” said Grove, “they had no idea about what the company or the industry was like, nor did they seem to care. . . . Fairchild was just crumbling. If you wish, the semiconductor division management consisted of twenty significant players: eight went to National, eight went into Intel, and four of them went to Alcoholics Anonymous or something.” Actually there were more than twenty and they went into startups all over the Valley; some twenty-six new semiconductor firms sprouted up between 1967 and 1970. “It got to the point,” recalled one man quoted in Dirk Hanson’s The New Alchemists, “where people were practically driving trucks over to Fairchild and loading up with employees.”

Source:

Gilder, George. Microcosm: The Quantum Revolution in Economics and Technology. Paperback ed. New York: Touchstone, 1990.

(Note: the first ellipsis was added; the others were in the original. The italics were also in the original.)