In Kirckcaldy, Gordon Brown, the man on the right, tries to persuade the natives to vote for the Labor Party. Source of the photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

In Kirckcaldy, Gordon Brown, the man on the right, tries to persuade the natives to vote for the Labor Party. Source of the photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Many years ago, we took the train from Edinburgh to spend a few hours in Kirkcaldy, the birthplace of Adam Smith. I was surprised at how little there was to honor Smith in the town where he was born and raised. There was a small cafe/theatre named after Smith. A small crystal shop sold some shot glasses with Smith’s image engraved on them. And there was a small plaque, above a no-parking sign, on the main street, at the spot where Smith’s family home had been.

I remember asking a very polite young father with two or three small children in tow, why there was so little of Smith in Kirckaldy? With a twinge of something like regret, he said that everyone in that part of Scotland supported Labor, and they saw Smith as supporting capitalism, and so did not like him much.

It was a crowded Saturday shopping day when Jeanette took my picture in front of the small plaque. Incredulous passers-by turned and glanced in my direction, probably wondering why the crazy American wanted his picture taken next to a no-parking sign.

For the sake of Kirkcaldy, and Britain, let us hope that Gordon Brown has read a bit of the work of his fellow Kirkcaldy native son:

(p. A10) KIRKCALDY, Scotland, April 30 — Gordon Brown, Britain’s presumed prime minister-to-be, is usually associated with a somewhat dour manner and a mastery of statistics. But here, he displays other skills — a bolt-on smile and a ready handshake to work sparse crowds between the discount stores on the High Street, asking parents with strollers whether their new babies are keeping them awake at night, and inquiring whether the men support the local Raith Rovers soccer team.

. . .

“This is a big choice on Thursday, between those who want to break up Britain and those who want to build up Scotland,” Mr. Brown, currently Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, told students at Adam Smith College, named for the 18th-century economist who was born here.

. . .

Mr. Brown, who is not standing in these elections, came to town, alongside the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth, to support the Scottish Labor campaign and resist the nationalists.

“I do not think the Scottish people want to see the breakup of the union” that makes up Britain, he said here in Kirkcaldy (pronounced kerr-CUDDY).

But advocates of independence say it would propel Scotland to a bright future, as viable as any other small European state.

For the full story, see:

ALAN COWELL. "Elections in Britain Reveal a Scottish Line in the Sand." The New York Times (Weds., May 2, 2007): A10.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Art Diamond in Kirkcaldy in 1994 at location (I think on High Street) where Adam Smith’s boyhood home used to be. (Photo by Jeanette Diamond.)

Art Diamond in Kirkcaldy in 1994 at location (I think on High Street) where Adam Smith’s boyhood home used to be. (Photo by Jeanette Diamond.)

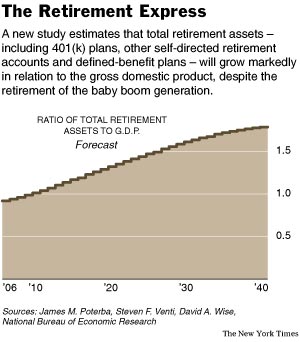

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below. A CVS pharmacy MinuteClinic. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

A CVS pharmacy MinuteClinic. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.  Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below. A former Swedish teacher who had been receiving government disability payments for being allergic to electricity. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

A former Swedish teacher who had been receiving government disability payments for being allergic to electricity. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.