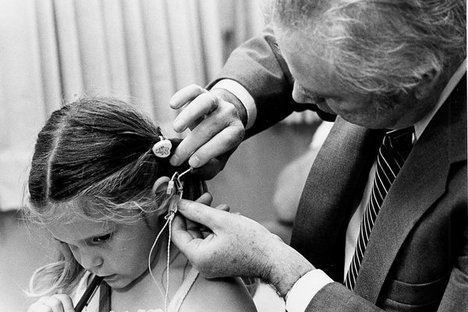

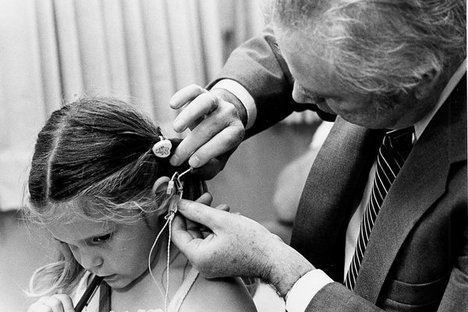

“Dr. William F. House in 1981 with Tracy Husted, the first pre-school-age child to get a cochlear implant.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT obituary quoted and cited below.

“Dr. William F. House in 1981 with Tracy Husted, the first pre-school-age child to get a cochlear implant.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT obituary quoted and cited below.

(p. 34) Dr. William F. House, a medical researcher who braved skepticism to invent the cochlear implant, an electronic device considered to be the first to restore a human sense, died on Dec. 7 at his home in Aurora, Ore. He was 89.

. . .

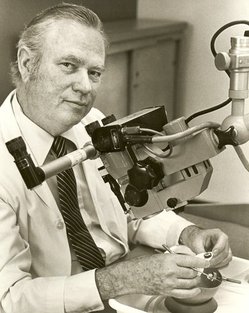

Dr. House pushed against conventional thinking throughout his career. Over the objections of some, he introduced the surgical microscope to ear surgery. Tackling a form of vertigo that doctors had believed was psychosomatic, he developed a surgical procedure that enabled the first American in space to travel to the moon. Peering at the bones of the inner ear, he found enrapturing beauty.

. . .

More than a decade would pass before the Food and Drug Administration approved the cochlear implant, but when it did, in 1984, Mark Novitch, the agency’s deputy commissioner, said, “For the first time a device can, to a degree, replace an organ of the human senses.”

One of Dr. House’s early implant patients, from an experimental trial, wrote to him in 1981 saying, “I no longer live in a world of soundless movement and voiceless faces.”

But for 27 years, Dr. House had faced stern opposition while he was developing the device. Doctors and scientists said it would not work, or not work very well, calling it a cruel hoax on people desperate to hear. Some said he was motivated by the prospect of financial gain. Some criticized him for experimenting on human subjects. Some advocates for the deaf said the device deprived its users of the dignity of their deafness without fully integrating them into the hearing world.

. . .

When his brother returned from West Germany with a surgical microscope, Dr. House saw its potential and adopted it for ear surgery; he is credited with introducing the device to the field. But again there was resistance. As Dr. House wrote in his memoir, “The Struggles of a Medical Innovator: Cochlear Implants and Other Ear Surgeries” (2011), some eye doctors initially criticized his use of a microscope in surgery as reckless and unnecessary for a surgeon with good eyesight.

For the full obituary, see:

DOUGLAS MARTIN. “Dr. William F. House, Inventor of Pioneering Ear-Implant Device, Dies at 89.” The New York Times, First Section (Sun., December 16, 2012): 34.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the obituary has the date December 15, 2012.)

Dr. House’s memoir is:

House, William F. The Struggles of a Medical Innovator: Cochlear Implants and Other Ear Surgeries. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011.

(Note: the copyright page of the book gives neither city nor name of publisher; the publisher in the reference is as given by Amazon.com.)

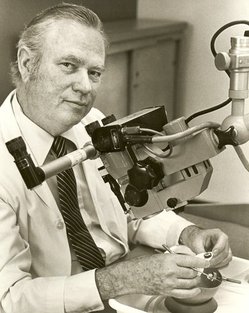

“Dr. William F. House sitting at an operating microscope.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT obituary quoted and cited above.