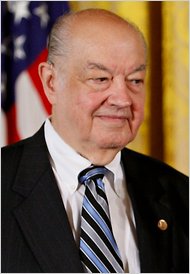

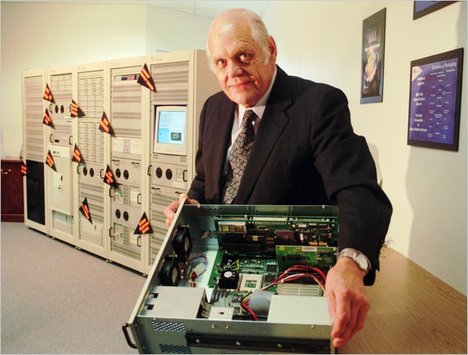

“Ken Olsen, the pioneering founder of DEC, in 1996.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Ken Olsen, the pioneering founder of DEC, in 1996.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

I believe in The Road Ahead, Bill Gates describes Ken Olsen as one of his boyhood heroes for having created a computer that could compete with the IBM mainframe. His hero failed to prosper when the next big thing came along, the PC. Gates was determined that he would avoid his hero’s fate, and so he threw his efforts toward the internet when the internet became the next big thing.

Christensen sometimes uses the fall of minicomputers, like Olsen’s Dec, to PCs as a prime example of disruptive innovation, e.g., in his lectures on disruptive innovation available online through Harvard. A nice intro lecture is viewable (but only using Internet Explorer) at: http://gsb.hbs.edu/fss/previews/christensen/start.html

(p. A22) Ken Olsen, who helped reshape the computer industry as a founder of the Digital Equipment Corporation, at one time the world’s second-largest computer company, died on Sunday. He was 84.

. . .

Mr. Olsen, who was proclaimed “America’s most successful entrepreneur” by Fortune magazine in 1986, built Digital on $70,000 in seed money, founding it with a partner in 1957 in the small Boston suburb of Maynard, Mass. With Mr. Olsen as its chief executive, it grew to employ more than 120,000 people at operations in more than 95 countries, surpassed in size only by I.B.M.

At its peak, in the late 1980s, Digital had $14 billion in sales and ranked among the most profitable companies in the nation.

But its fortunes soon declined after Digital began missing out on some critical market shifts, particularly toward the personal computer. Mr. Olsen was criticized as autocratic and resistant to new trends. “The personal computer will fall flat on its face in business,” he said at one point. And in July 1992, the company’s board forced him to resign.

For the full obituary, see:

GLENN RIFKIN. “Ken Olsen, Founder of the Digital Equipment Corporation, Dies at 84.” The New York Times (Tues., February 8, 2011): A22.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated February 7, 2011 and has the title “Ken Olsen, Who Built DEC Into a Power, Dies at 84.”)

Gates writes in autobiographical mode in the first few chapters of:

Gates, Bill. The Road Ahead. New York: Viking Penguin, 1995.

Christensen’s mature account of disruptive innovation is best elaborated in:

Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.