As of 6/22/11, space is still available in the graduate economics, MBA, and upper level undergraduate economics sections of the seminar.

Category: Entrepreneurship

“The Century’s Most Daring and Iconic Building Was Entrusted to a Gardener”

(p. 10) . . . the risks were considerable and keenly felt, yet after only a few days of fretful hesitation the commissioners approved Paxton’s plan. Nothing–really, absolutely nothing–says more about Victorian Britain and its capacity for brilliance than that the century’s most daring and iconic building was entrusted to a gardener. Paxton’s Crystal Palace required no bricks at all–indeed, no mortar, no cement, no foundations. It was just bolted together and sat on the ground like a tent. This was not merely an (p. 11) ingenious solution to a monumental challenge but also a radical departure from anything that had ever been tried before.

Source:

Bryson, Bill. At Home: A Short History of Private Life. New York: Doubleday, 2010.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Moral: In a Crisis You Need Resilience and the Ability to Improvise More than You Need Detailed Advance Plans

(p. D1) When the Three Mile Island nuclear generating station along the Susquehanna River seemed on the verge of a full meltdown in March 1979, Gov. Richard L. Thornburgh of Pennsylvania asked a trusted aide to make sure that the evacuation plans for the surrounding counties would work.

The aide came back ashen faced. Dauphin County, on the eastern shore of the river, planned to send its populace west to safety over the Harvey Taylor Bridge.

“All well and good,” Mr. Thornburgh said in a recent speech, “except for the fact that Cumberland County on the west shore of the river had adopted an evacuation plan that would funnel all exiting traffic eastbound over — you guessed it — the same Harvey Taylor Bridge.”

. . .

(p. D4) Brian Wolshon, the director of the Gulf Coast Center for Evacuation and Transportation Resiliency, said that he was analyzing one county’s emergency plans that seemed to have every detail covered.“It was a wonderful report, with plans to move senior citizens out of care facilities and even out of hospitals, and they had signed contracts with bus and ambulance providers,” said Dr. Wolshon, who is also a professor at Louisiana State University. “But that same low-cost provider had the same contract with the county next door, and they had the capacity to evacuate only one of these counties.”

For the full story, see:

GARDINER HARRIS. “Dangers of Leaving No Resident Behind.” The New York Times (Tues., March 22, 2011): D1 & D4.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated March 21, 2011.)

Entrepreneur Defends His Store with Gun

“Anthony Spinelli, outside his store in the Bronx on Thursday, was called brave for shooting a man suspected of trying to rob his shop.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A23) On Arthur Avenue, a group of men piled out of Pasquale’s Rigoletto restaurant onto the sidewalk to pay their respects to a sudden local hero.

“Anthony, we love you,” they shouted across the street.

They summed up the local sentiment about a man, Anthony Spinelli, celebrated for protecting his livelihood. On Wednesday, Mr. Spinelli pulled one of two licensed guns in the store, and shot one of the three people suspected of trying to rob his Arthur Avenue jewelry store at gunpoint.

The Bronx neighborhood seemed energized by the event, which people here saw as a testament to the toughness of one of the last Italian neighborhoods in New York City.

“You don’t come in and try to take a man’s livelihood,” said Nick Lousido, who called himself a neighborhood regular. “His family’s store has 50 years on this block, they’re going to come in and rob him?”

On Thursday, Mr. Spinelli, 49, had returned to his shop and sized up the broken front windows and the mess inside. He said that a man and woman had entered his store, and the man had held a gun to his head while the woman had gone through jewelry drawers and stuffed jewelry into a bag. He said he had feared for his life, and that he was still shaken.

. . .

Next door to Mr. Spinelli’s shop is M & M Painter Supplies, which has photographs of Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa next to a paint color chart on the wall.

“He’s a very brave man,” said the store owner, Ernie Verino. “He had the gun, and it takes guts to use it.”

For the full story, see:

COREY KILGANNON. “Merchant Shooting to Defend His Store Is Celebrated as Hero of Arthur Avenue.” The New York Times (Fri., February 18, 2011): A23.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated February 17, 2011 and has the title “After Shooting, Merchant Is Hero of Arthur Avenue.”)

“Big Money Is Dumb Money”

“Other People’s Money” is a short story that appears in Cory Doctorow’s short story collection With a Little Help.

(p. C7) Venture capitalists? Forget them, says “Other People’s Money.” Big money is dumb money. Much easier, says one old-lady manufacturer to a smart young gigafund manager, for her to make and market her own product, and keep the money (just like Mr. Doctorow), than for him to find and fund a hundred products and take a rake-off. He only deals in six-figure multiples, and that’s no good: not nimble enough. And he has to get a return on all those billions, poor outdated soul.

For the full review, see:

TOM SHIPPEY. “The Author as Agent of Change; Cory Doctorow has big ideas about the future of technology–and how it can empower writers.” The New York Times (Sat., MAY 21, 2011): C7.

The book of short stories is:

Doctorow, Cory. With a Little Help.

To Burst Higher Ed Bubble, Peter Thiel Pays Students to Drop Out

“Peter Thiel.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B4) Parents, do you hope that your children have the chance to become like Peter Thiel, the PayPal co-founder, Facebook investor and hedge fund manager? If so, Mr. Thiel suggests that you encourage them to drop out of school. In fact, he will help by paying them to do it.

On Wednesday, the Thiel Foundation, funded by Mr. Thiel, announced the first group of Thiel Fellows, 24 people under 20 who have agreed to drop out of school in exchange for a $100,000 grant and mentorship to start a tech company.

More than 400 people applied. The winners include Laura Deming, 17, who is developing antiaging therapies; Faheem Zaman, 18, who is building mobile payment systems for developing countries; and John Burnham, 18, who is working on extracting minerals from asteroids and comets.

. . .

Mr. Thiel, a contrarian investor and libertarian known for his controversial views, knows that suggesting that education is not always worth it strikes at the core of many Americans’ beliefs. But that is exactly why is he doing it.

“We’re not saying that everybody should drop out of college,” he said. The fellows agree to stop getting a formal education for two years but can always go back to school. The problem, he said, is that “in our society the default assumption is that everybody has to go to college.”

“I believe you have a bubble whenever you have something that’s overvalued and intensely believed,” Mr. Thiel said. “In education, you have this clear price escalation without incredible improvement in the product. At the same time you have this incredible intensity of belief that this is what people have to do. In that way it seems very similar in some ways to the housing bubble and the tech bubble.”

. . .

“What I really liked about this program is it’s giving a lot of people who maybe wouldn’t get into Harvard an opportunity to participate in something just as selective and just as valuable and just as educational,” Mr. Burnham said. “It’s giving them that opportunity even though their personalities and characters don’t quite fit the academic mold.”

His father, Stephen Burnham, said the decision for his son to skip college, at least for now, was uncontroversial.

“There’s a lot of other stuff that you get in college and I would say that would be useful for John,” he said. “But I would say in four years there’s a big opportunity cost there if you could be out starting your career doing something that could change the world.”

For the full story, see:

CLAIRE CAIN MILLER. “Changing the World by Dropping Out.” The New York Times (Mon., May 30, 2011): B4.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated May 25 (sic), 2011, has the title “Want Success in Silicon Valley? Drop Out of School,” and is longer than the published version. Most of what is quoted above appears in both the published and online versions, but some (most notably the paragraph on the education bubble and the quotes from Stephen Burnham) appear only in the online verison.)

“Surprisingly Weak Correlation” Between Measures of Maximum Performance and Typical Performance

(p. C12) In the early 1980s, Paul Sackett, a psychologist at the University of Minnesota, began measuring the speed of cashiers at supermarkets. Workers were told to scan a few dozen items as quickly as possible while a scientist timed them. Not surprisingly, some cashiers were much faster than others.

But Mr. Sackett realized that this assessment, which lasted just a few minutes, wasn’t the only way to measure cashier performance. Electronic scanners, then new in supermarkets, could automatically record the pace of cashiers for long stretches of time. After analyzing this data, it once again became clear that levels of productivity varied greatly.

Mr. Sackett had assumed that these separate measurements would generate similar rankings. Those cashiers who were fastest in the short test should also be the fastest over the long term. But instead he found a surprisingly weak correlation between the rankings, leading him to distinguish between two types of personal assessment. One measures “maximum performance”: People who know they’re being tested are highly motivated and focused, just like those cashiers scanning a few items while being timed.

The other type measures “typical performance”–measured over long periods of time, as when Mr. Sackett recorded the speed of cashiers who didn’t know they were being watched. In this sort of test, character traits that have nothing to do with maximum performance begin to influence the outcome. Cashiers with speedy hands won’t have fast overall times if they take lots of breaks.

. . .

The problem, of course, is that students don’t reveal their levels of grit while taking a brief test. Grit can only be assessed by tracking typical performance for an extended period. Do people persevere, even in the face of difficulty? How do they act when no one else is watching? Such traits often matter more than raw talent. We hear about them in letters of recommendation, but hard numbers take priority.

The larger lesson is that we’ve built our society around tests of performance that fail to predict what really matters: what happens once the test is over.

For the full commentary, see:

JONAH LEHRER. “Measurements That Mislead; From the SAT to the NFL, the problem with short-term tests.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., APRIL 2, 2011): C12.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The classic article correlating maximum and typical performance, is:

Sackett, Paul R., Sheldon Zedeck, and Larry Fogli. “Relationships between Measures of Typical and Maximum Performance.” Journal of Applied Psychology 73 (1988): 482-86.

To Teach the Truth, the Best Teachers Must Become “Canny Outlaws”

Source of book image: http://www.swarthmore.edu/Images/news/practical_wisdom.jpg

(p. 170) Walking into Mr. Drew’s economics class, researchers might have interrupted a board meeting of the student-run start-up company that was at the heart of his course. Drawing on his own experience in industry, Mr. Drew taught students economic principles in a way that made sense to them because they were researching

potential products they would actually sell (a mug with the school logo; a T-shirt designed by a student graphics team). They were conducting market surveys, accumulating capital, making decisions about the scale of investment, the risk, the profits.

. . .

In Houston. the magnet schools were forced to reorganize to prepare for the coming White-Perot reforms. McNeil changed her study. The new question was: How would these teachers cope with a curriculum that was test-driven?

. . .

Mr. Drew’s economics class did not conform to the proficiency sequence and he had to drop the course, except as an elective.

. . .

The paperwork required by such new requirements–to assure the bureaucracy that teachers were teaching by the rules–discouraged individualized time spent with students and robbed time previously devoted to planning and assessing lessons. The requirements created the same kind of time bind Wong observed when such requirements were imposed on military trainers. (p. 171) And, as in the case of the new military training model, the new requirements discouraged flexibility, adaptability, and creativity.

McNeil found that many of the experienced teachers fought back. They became canny outlaws, or creative saboteurs, dodging the “law,” finding ways to cover the “proficiencies” with great efficiency and squirreling away time to sneak real education back in at the margins of the standardized system, sometimes even conspiring with their students or teaching them how to “game” the system. Mr. Drew taught his students that economic cycles vary in length and intensity, but in the test prep period, he told them to forget this because the official answer was that each cycle lasts eighteen months. There was a danger that students who learned to look beyond the obvious, to ask “what if,” to look for the exceptions to the rules, would do badly on the tests.

. . .

The ability of wise teachers to operate as canny outlaws is most seriously constrained when a highly scripted curriculum comes riding into town on the heels of high-stakes standardized tests. By prescribing, step by step, what to say and do each day to prepare students for these tests, such lockstep curricula pose a serious challenge to professional discretion. Yet even under these adverse conditions, in many schools there are canny

outlaws who find ways to avoid being channeled.

Source:

Schwartz, Barry, and Kenneth Sharpe. Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to Do the Right Thing. New York: Riverhead Books, 2010.

(Note: ellipses added.)

The McNeil book mentioned above is:

Linda, McNeil. Contradictions of School Reform: Educational Costs of Standardized Testing, Critical Social Thought. New York: Routledge, 2000.

The Wong report mentioned above is:

Wong, Leonard. “Stifled Innovation? Developing Tomorrow’s Leaders Today.” Strategic Studies Institute Monograph, April 1, 2002.

Source of book image: http://i43.tower.com/images/mm101682007/contradictions-school-reform-educational-costs-standardized-testing-linda-m-mcneil-paperback-cover-art.jpg

The “Disneyland Dream” Lives

Liberal columnist Frank Rich writes of the home movie “Disneyland Dream”—with a measure of eloquence, but unfortunately also with a measure of condescension and sarcasm. In the end, he believes the dream is dead.

But Rich is wrong. Disneyland is still the happiest place on earth, and Walt Disney’s entrepreneurial spirit is also still alive.

Here are a couple of the more eloquent bits of Rich (though not entirely devoid of sarcasm):

(p. 14) “Disneyland Dream” was made in the summer of 1956, shortly before the dawn of the Kennedy era. You can watch it on line at archive.org or on YouTube. Its narrative is simple. The young Barstow family of Wethersfield, Conn. — Robbins; his wife, Meg; and their three children aged 4 to 11 — enter a nationwide contest to win a free trip to Disneyland, then just a year old. The contest was sponsored by 3M, which asked contestants to submit imaginative encomiums to the wonders of its signature product. Danny, the 4-year-old, comes up with the winning testimonial, emblazoned on poster board: “I like ‘Scotch’ brand cellophane tape because when some things tear then I can just use it.”

. . .

. . . The Barstows accept as a birthright an egalitarian American capitalism where everyone has a crack at “upper class” luxury if they strive for it (or are clever enough to win it). It’s an America where great corporations like 3M can be counted upon to make innovative products, sustain an American work force, and reward their customers with a Cracker Jack prize now and then. The Barstows are delighted to discover that the restrooms in Fantasyland are marked “Prince” and “Princess.” In America, anyone can be royalty, even in the john.

“Disneyland Dream” is an irony-free zone. “For our particular family at that particular time, we agreed with Walt Disney that this was the happiest place on earth,” Barstow concludes at the film’s end, from his vantage point of 1995. He sees himself as part of “one of the most fortunate families in the world to have this marvelous dream actually come true” and is “forever grateful to Scotch brand cellophane tape for making all this possible for us.”

For the full commentary, see:

FRANK RICH. “Who Killed the Disneyland Dream?” The New York Times, Week in Review Section (Sun., December 25, 2010): 14.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary is dated December 25, 2010.

Part 1 of “Disneyland Dream” via YouTube’s “embed” feature:

Part 2 of “Disneyland Dream” via YouTube’s “embed” feature:

Part 3 of “Disneyland Dream” via YouTube’s “embed” feature:

Part 4 of “Disneyland Dream” via YouTube’s “embed” feature:

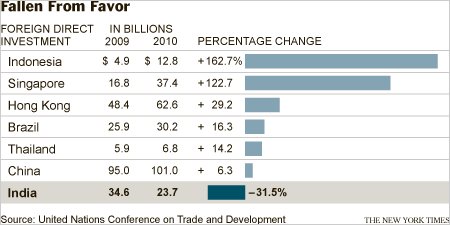

Corruption, Inefficiency, Inflation and Bad Policies Lead to Decline in Foreign Investment in India

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B1) While inefficiency and bureaucracy are nothing new in India, analysts and executives say foreign investors have lately been spooked by a highly publicized government corruption scandal over the awarding of wireless communications licenses. Another reason for thinking twice is a corporate tax battle between Indian officials and the British company Vodafone now before India’s Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the inflation rate — 8.2 percent and rising — seems beyond the control of India’s central bank and has done nothing to reassure foreign investors.

And multinationals initially lured by India’s growth narrative may find that the realities of the Indian marketplace tell a more vexing story. Some companies, including the insurer MetLife and the retailing giant Wal-Mart, for example, are eager to invest and expand here but have been waiting years for policy makers to let them.

For the full story, see:

VIKAS BAJAJ. “Foreign Investment Ebbs in India.” The New York Times (Fri., February 25, 2011): B1 & B6.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated February 24, 2011.)

“Gambles on Original Concepts Paid Off”

“One surprise hit was “Inception,” with Leonardo DiCaprio.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“One surprise hit was “Inception,” with Leonardo DiCaprio.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

I thought the movie “Inception” was a wonderful, intellectual and adventure thrill ride. And if memory serves, what they were trying to instill in the conflicted inheritor of a monopoly, was that he should become more entrepreneurial.

(p. B1) As Hollywood plowed into 2010, there was plenty of clinging to the tried and true: humdrum remakes like “The Wolfman” and “The A-Team”; star vehicles like “Killers” with Ashton Kutcher and “The Tourist” with Angelina Jolie and Johnny Depp; and shoddy sequels like “Sex and the City 2.” All arrived at theaters with marketing thunder intended to fill multiplexes on opening weekend, no matter the quality of the film. “Sex and the City 2,” for example, had marketed “girls’ night out” premieres and bottomless stacks of merchandise like thong underwear.

But the audience pushed back. One by one, these expensive yet middle-of-the-road pictures delivered disappointing results or flat-out flopped. Meanwhile, gambles on original concepts paid off. “Inception,” a complicated thriller about dream invaders, racked up more than $825 million in global ticket sales; “The Social Network” has so far delivered $192 million, a stellar result for a highbrow drama.

As a result, studios are finally and fully conceding that moviegoers, armed with Facebook and other networking tools and concerned about escalating ticket prices, are holding them to higher standards. The product has to be good.

For the full story, see:

BROOKS BARNES. “Hollywood Moves Away From Middlebrow.” The New York Times (Mon., December 27, 2010): B1 & B5.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated December 26, 2010 and has the title “Hollywood Moves Away From Middlebrow.”)