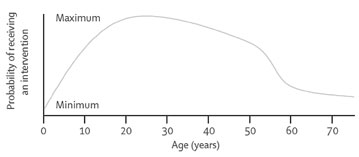

“The Reaper Curve: Ezekiel Emanuel used the above chart in a Lancet article to illustrate the ages on which health spending should be focused.” Source of caption and graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. A15) Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, health adviser to President Barack Obama, is under scrutiny. As a bioethicist, he has written extensively about who should get medical care, who should decide, and whose life is worth saving. Dr. Emanuel is part of a school of thought that redefines a physician’s duty, insisting that it includes working for the greater good of society instead of focusing only on a patient’s needs. Many physicians find that view dangerous, and most Americans are likely to agree.

The health bills being pushed through Congress put important decisions in the hands of presidential appointees like Dr. Emanuel. They will decide what insurance plans cover, how much leeway your doctor will have, and what seniors get under Medicare. Dr. Emanuel, brother of White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, has already been appointed to two key positions: health-policy adviser at the Office of Management and Budget and a member of the Federal Council on Comparative Effectiveness Research. He clearly will play a role guiding the White House’s health initiative.

. . .

In the Lancet, Jan. 31, 2009, Dr. Emanuel and co-authors presented a “complete lives system” for the allocation of very scarce resources, such as kidneys, vaccines, dialysis machines, intensive care beds, and others. “One maximizing strategy involves saving the most individual lives, and it has motivated policies on allocation of influenza vaccines and responses to bioterrorism. . . . Other things being equal, we should always save five lives rather than one.

“However, other things are rarely equal–whether to save one 20-year-old, who might live another 60 years, if saved, or three 70-year-olds, who could only live for another 10 years each–is unclear.” In fact, Dr. Emanuel makes a clear choice: “When implemented, the complete lives system produces a priority curve on which individuals aged roughly 15 and 40 years get the most substantial chance, whereas the youngest and oldest people get changes that are attenuated (see Dr. Emanuel’s chart nearby).

Dr. Emanuel concedes that his plan appears to discriminate against older people, but he explains: “Unlike allocation by sex or race, allocation by age is not invidious discrimination. . . . Treating 65 year olds differently because of stereotypes or falsehoods would be ageist; treating them differently because they have already had more life-years is not.”

For the full commentary, see:

BETSY MCCAUGHEY. “Obama’s Health Rationer-in-Chief; White House health-care adviser Ezekiel Emanuel blames the Hippocratic Oath for the ‘overuse’ of medical care.” The Wall Street Journal (Thurs., August 27, 2009): A15.

(Note: first ellipsis added; second and third ellipses in original.)

The article that was the original source for the graph above, is:

Persad, Govind, Alan Wertheimer, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel. “Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions.” The Lancet 373, no. 9661 (Jan. 31, 2009): 423-31.