(p. A19) . . . , there is one way to create a lot more jobs without spending federal money. Let’s import them. More precisely, let’s import the people who create them: entrepreneurs.

A bipartisan bill that would begin to do just that was introduced on Feb. 24 by Sens. John Kerry (D., Mass.) and Richard Lugar (R., Ind.). Their “Startup Visa Act” would create a new, two-year visa for immigrant entrepreneurs whose firms attract at least $250,000 in financing from American angel investors or venture capital firms.

. . .

Here’s a way to improve on the Kerry-Lugar plan. Create a true “job creator’s visa,” one tied directly and only to job creation by new immigrant entrepreneurs. The visa could be a temporary one for immigrants already here on another visa who establish a business. It could then be extended if the firm hires at least one American non-family resident. The visa should become permanent once the enterprise crosses a certain job threshold (such as five or 10 workers). But it would not be tied to financing.

. . .

Google was founded by Sergey Brin, a Russian immigrant, and American Larry Page by borrowing funds from their own credit cards. Why on earth would we want to create an entrepreneurs’ visa that couldn’t let in the future Sergey Brin?

For the full commentary, see:

ROBERT E. LITAN. “Visas for the Next Sergey Brin; To create more jobs, let’s import more employers.” The Wall Street Journal (Mon., MARCH 8, 2010): A19.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated MARCH 7, 2010.)

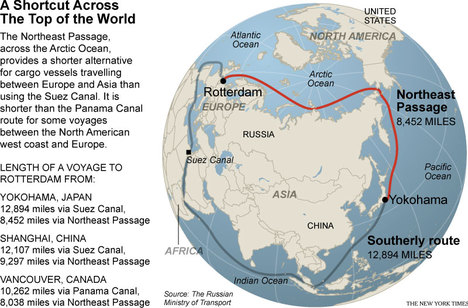

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.  Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from: