Source for the image of the Moment issue cover, on left: http://www.momentmag.com/issue/index.html Source for the image of the first page of the article, on right: online version of the Moment article cited below.

Source for the image of the Moment issue cover, on left: http://www.momentmag.com/issue/index.html Source for the image of the first page of the article, on right: online version of the Moment article cited below.

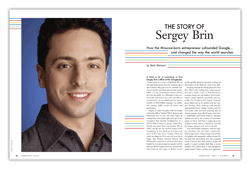

Sergey, who turned six that summer, remembers what followed as simply “unsettling”—literally so. “We were in different places from day to day,” he says. The journey was a blur. First Vienna, where the family was met by representatives of HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, which helped thousands of Eastern European Jews establish new lives in the free world. Then, on to the suburbs of Paris, where Michael’s “unofficial” Jewish Ph.D. advisor, Anatole Katok, had arranged a temporary research position for him at the Institut des Hautes Etudes Scientifiques. Katok, who had emigrated the year before with his family, looked after the Brins and paved the way for Michael to teach at Maryland.

When the family finally landed in America on October 25, they were met at New York’s Kennedy Airport by friends from Moscow. Sergey’s first memory of the United States was of sitting in the backseat of the car, amazed at all the giant automobiles on the highway as their hosts drove them home to Long Island.

The Brins found a house to rent in Maryland—a simple, cinder-block structure in a lower-middle-class neighborhood not far from the university campus. With a $2,000 loan from the Jewish community, they bought a 1973 Ford Maverick. And, at Katok’s suggestion, they enrolled Sergey in Paint Branch Montessori School in Adelphi, Maryland.

He struggled to adjust. Bright-eyed and bashful, with only a rudimentary knowledge of English, Sergey spoke with a heavy accent when he started school. “It was a difficult year for him, the first year,” recalls Genia. “We were constantly discussing the fact we had been told that children are like sponges, that they immediately grasp the language and have no problem, and that wasn’t the case.”

Patty Barshay, the school’s director, became a friend and mentor to Sergey and his parents. She invited them to a party at her house that first December (“a bunch of Jewish people with nothing to do on Christmas Day”) and wound up teaching Genia how to drive. Everywhere they turned, there was so much to take in. “I remember them inviting me over for dinner one day,” Barshay says, “and I asked Genia, ‘What kind of meat is this?’ She had no idea. They had never seen so much meat” as American supermarkets offer.

When I ask about her former pupil, Barshay lights up, obviously proud of Sergey’s achievements. “Sergey wasn’t a particularly outgoing child,” she says, “but he always had the self-confidence to pursue what he had his mind set on.”

He gravitated toward puzzles, maps and math games that taught multiplication. “I really enjoyed the Montessori method,” he tells me. “I could grow at my own pace.” He adds that the Montessori environment—which gives students the freedom to choose activities that suit their interests—helped foster his creativity.

“He was interested in everything,” Barshay says, but adds, “I never thought he was any brighter than anyone else.”

For the full story, see:

"Sergei and Pyotr Leontiev are reunited on the Russian TV show, ‘Zhdi Menya.’" Source of the caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

"Sergei and Pyotr Leontiev are reunited on the Russian TV show, ‘Zhdi Menya.’" Source of the caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below. The actor who hosts "Zhdi Menya" ("Wait for Me"). Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

The actor who hosts "Zhdi Menya" ("Wait for Me"). Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

A vacuum tube used in guitar amplifiers, that was produced in the factory that Mike Matthews owned. Source of photo:

A vacuum tube used in guitar amplifiers, that was produced in the factory that Mike Matthews owned. Source of photo:  Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.