“Fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient astronomical computer built by the Greeks around 80 B.C. It was found on a shipwreck by sponge divers in 1900, and its exact function still eludes scholars.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient astronomical computer built by the Greeks around 80 B.C. It was found on a shipwreck by sponge divers in 1900, and its exact function still eludes scholars.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A12) After a closer examination of a surviving marvel of ancient Greek technology known as the Antikythera Mechanism, scientists have found that the device not only predicted solar eclipses but also organized the calendar in the four-year cycles of the Olympiad, forerunner of the modern Olympic Games.

The new findings, reported Wednesday in the journal Nature, also suggested that the mechanism’s concept originated in the colonies of Corinth, possibly Syracuse, on Sicily. The scientists said this implied a likely connection with Archimedes.

Archimedes, who lived in Syracuse and died in 212 B.C., invented a planetarium calculating motions of the Moon and the known planets and wrote a lost manuscript on astronomical mechanisms. . . .

. . .

Only now, applying high-resolution imaging systems and three-dimensional X-ray tomography, have experts been able to decipher inscriptions and reconstruct functions of the bronze gears on the mechanism. The latest research has revealed details of dials on the instrument’s back side, including the names of all 12 months of an ancient calendar.

In the journal report, the team led by the mathematician and filmmaker Tony Freeth of the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, in Cardiff, Wales, said the month names “are unexpectedly of Corinthian origin,” which suggested “a heritage going back to Archimedes.”

For the full story, see:

JOHN NOBLE WILFORD. “Discovering How Greeks Computed in 100 B.C.” The New York Times (Thurs., July 31, 2008): A12.

(Note: ellipses added.)

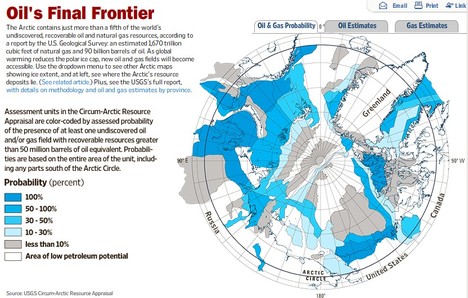

Source of the graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of the graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.