Source of report cover image: http://www.pacificresearch.org/pub/sab/entrep/2007/Jackpot_Justice/index.html

Source of report cover image: http://www.pacificresearch.org/pub/sab/entrep/2007/Jackpot_Justice/index.html

(p. A18) How does the legal system extract such an astounding amount from our economy? We applied the rent-seeking theory of transfers from economic science to pick up where past studies — including the highly regarded Tillinghast-Towers Perrin study — leave off. We began by examining the static costs of litigation — including annual damage awards, plaintiff attorneys’ fees, defense costs, administrative costs and deadweight costs from torts such as product liability cases, medical malpractice litigation and class action lawsuits. The annual static costs, $328 billion per year, are well in excess of previous Tillinghast estimates.

But $328 billion is only the beginning. After all, litigation doesn’t just transfer wealth, it also changes behavior, and often in economically unproductive ways. Any true estimate of the costs of America’s tort system must also include these dynamic costs of litigation — the impact on research and development spending, the costs of defensive medicine and the related rise in health-care spending and reduced access to health care, and the loss of output from deaths due to excess liability.

. . .

Based on data from previous studies, we determined that more than 77,000 people would have been alive today and contributing to the workforce, but are not because of a failure to enact comprehensive tort reforms in the states. The cost of foregone output from these lost workers is more than $7 billion each year.

What we’re left with, then, are annual dynamic costs of $537 billion resulting from our litigation system. Add that to the static costs of $328 billion and you arrive at the total of over $865 billion per year.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

McQuillan, Abryamyan, along with Anthony P. Archie, have co-authored a report entitled Jackpot Justice: The True Cost of America’s Tort System that elaborates on many of the issues sketched in the commentary excerpted above. You can download a free PDF copy at: http://www.pacificresearch.org/pub/sab/entrep/2007/Jackpot_Justice/Jackpot_Justice.pdf

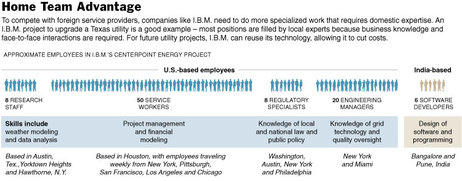

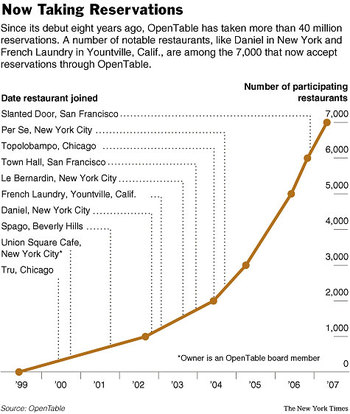

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of NYT article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of NYT article cited above.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above. Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

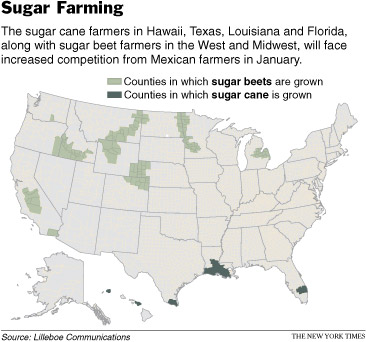

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.