Source of the image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of the image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Below are some excerpts from one of the unique, sometimes funny, sometimes inspiring, front page stories that are a signature feature of the Wall Street Journal.

Rupert Murdoch, the new owner of the WSJ, is rumored in the press to dislike stories such as the one quoted below. I hope the rumors are wrong.

(p. A1) MASITALA, Malawi — On a continent woefully short of electricity, 20-year-old William Kamkwamba has a dream: to power up his country one windmill at a time.

So far, he has built three windmills in his yard here, using blue-gum trees and bicycle parts. His tallest, at 39 feet, towers over this windswept village, clattering away as it powers his family’s few electrical appliances: 10 six-watt light bulbs, a TV set and a radio. The machine draws in visitors from miles around.

. . .

(p. A13) The contraption causing all the fuss is a tower made from lashed-together blue-gum tree trunks. From a distance, it resembles an old oil derrick. For blades, Mr. Kamkwamba used flattened plastic pipes. He built a turbine from spare bicycle parts. When the wind kicks up, the blades spin so fast they rock the tower violently back and forth.

Mr. Kamkwamba’s wind obsession started six years ago. He wasn’t going to school anymore because his family couldn’t afford the $80-a-year tuition.

When he wasn’t helping his family farm groundnuts and soybeans, he was reading. He stumbled onto a photograph of a windmill in a text donated to the local library and started to build one himself. The project seemed a waste of time to his parents and the rest of Masitala.

"At first, we were laughing at him," says Agnes Kamkwamba, his mother. "We thought he was doing something useless."

The laughter ended when he hooked up his windmill to a thin copper wire, a car battery and a light bulb for each room of the family’s main house.

The family soon started enjoying the trappings of modern life: a radio and, more recently, a TV. They no longer have to buy paraffin for lantern light. Two of Mr. Kamkwamba’s six sisters stay up late studying for school.

"Our lives are much happier now," Mrs. Kamkwamba says.

The new power also attracted a swarm of admirers. Last November, Hartford Mchazime, a Malawian educator, heard about the windmill and drove out to the Kamkwamba house with some reporters. After the news hit the blogosphere, a group of entrepreneurs scouting for ideas in Africa located Mr. Kamkwamba. Called TED, the group, which invites the likes of Al Gore and Bono to share ideas at conferences, invited him to a brainstorming session earlier this year.

In June, Mr. Kamkwamba was onstage at a TED conference in Tanzania. (TED stands for Technology Entertainment Design). "I got information about a windmill, and I try and I made it," he said in halting English to a big ovation. After the conference, a group of entrepreneurs, African bloggers and venture capitalists — some teary-eyed at the speech — pledged to finance his education.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

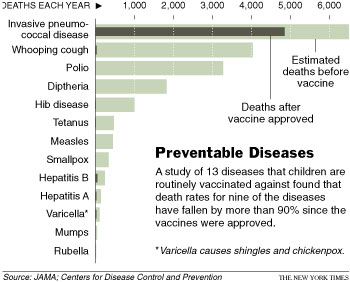

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.