Michael Crichton speaking on environmentalism at the Fairmont Hotel on September 15, 2003. Source of photo: Bill Adams’ posting at http://www.pbase.com/bill_adams/image/21439440

The papers announced yesterday (11/6/08) that Michael Crichton had died of cancer a couple of days earlier (11/4/08).

I had mixed feelings about his stories. On the one hand, they seemed mainly to stir up unrealistic fears about technology, which I see as mainly a benefit to humanity. On the other hand, they often involved intelligent heroes who struggled against danger, and won (or at least partly won).

Crichton’s best story may have been one of his last, State of Fear. In that book, he took on the environmental movement, and showed in a powerful appendix, how some scientists and scientific institutions have failed us, by creating fear that is not grounded in the free exchange of ideas and evidence.

Crichton did not have to take on this issue—it earned him vituperative enemies, and probably lost him some readers. But in the end, he too was an intelligent hero who struggled against danger—the danger of politically correct closed minds.

Michael Crichton, Rest in Peace.

P.S.: Crichton had some scientific credentials. Here are a couple of interesting facts about his life:

(p. A27) At Harvard, after a professor criticized his writing style, the younger Mr. Crichton changed his major from English to anthropology and graduated summa cum laude in 1964. He then spent a year teaching anthropology on a fellowship at Cambridge University. In 1966 he entered Harvard Medical School and began writing on the side to help pay tuition.

. . .

In 1969, after earning his medical degree, Mr. Crichton moved to the La Jolla section of San Diego and spent a year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Already inclining toward a writing career, he tilted decisively with “The Andromeda Strain,” a medical thriller about a group of scientists racing against time to stop the spread of a lethal organism from outer space code-named Andromeda.

For the full obituary, see:

WILLIAM GRIMES. “Michael Crichton, Author of Thrillers, Dies at 66.” The New York Times (Thurs., November 5, 2008): A27.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Michael Crichton during an April 11, 2002 lecture at the Harvard Medical School (from which he graduated). Source of photo: http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/04.18/11-crichton.html

Michael Crichton during an April 11, 2002 lecture at the Harvard Medical School (from which he graduated). Source of photo: http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/04.18/11-crichton.html

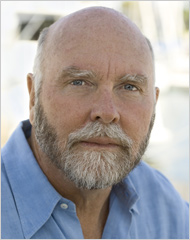

J. Craig Venter. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

J. Craig Venter. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.