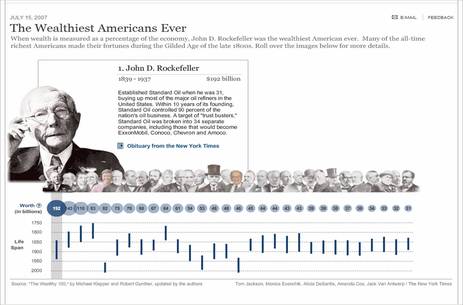

Source: screen capture of a flash animated graphic that appears in the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. The flash animated graphic allows you to move your cursor along the circles representing wealth, and at the top of the graphic appears the picture and a brief bio of the person who owned that amount of wealth (such as Rockefeller in the screen capture above).

Source: screen capture of a flash animated graphic that appears in the online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. The flash animated graphic allows you to move your cursor along the circles representing wealth, and at the top of the graphic appears the picture and a brief bio of the person who owned that amount of wealth (such as Rockefeller in the screen capture above).

(p. 18) Mr. Weill’s beginnings were . . . inauspicious. A son of immigrants from Poland, raised in Brooklyn, a so-so college student, he landed on Wall Street in a low-level job in the 1950s. Harnessing entrepreneurial energy, deftness as a deal maker and an appetite for risk, with a rising stock market pulling him along, he built a financial empire that, in his view, successfully broke through the stultifying constraints that flowed from the New Deal. They were constraints not just on what business could or could not do, but on every high earner’s take-home pay.

“I once thought how lucky the Carnegies and the Rockefellers were because they made their money before there was an income tax,” Mr. Weill said, never believing in his younger days that deregulation and tax cuts, starting in the late 1970s, would bring back many of the easier conditions of the Gilded Age. “I felt that everything of any great consequence was really all made in the past,” he said. “That turned out not to be true and it is not true today.”

The Question of Talent

Other very wealthy men in the new Gilded Age talk of themselves as having a flair for business not unlike Derek Jeter’s “unique talent” for baseball, as Leo J. Hindery Jr. put it. “I think there are people, including myself at certain times in my career,” Mr. Hindery said, “who because of their uniqueness warrant whatever the market will bear.”

He counts himself as a talented entrepreneur, having assembled from scratch a cable television sports network, the YES Network. “Jeter makes an unbelievable amount of money,” said Mr. Hindery, who now manages a private equity fund, “but you look at him and you say, ‘Wow, I cannot find another ballplayer with that same set of skills.’ ”

. . .

The New Tycoons

The new Gilded Age has created only one fortune as large as those of the Rockefellers, the Carnegies and the Vanderbilts — that of Bill Gates, according to various compilations. His net worth, measured as a share of the economy’s output, ranks him fifth among the 30 all-time wealthiest American families, just ahead of Carnegie. Only one other living billionaire makes the cut: Warren E. Buffett, in 16th place.

. . .

“I don’t think it is unreasonable,” he said, “for the C.E.O. of a company to realize 3 to 5 percent of the wealth accumulation that shareholders realize.”

That strikes Robert C. Pozen as a reasonable standard. He made a name for himself — and a fortune — overseeing the investment department at Fidelity.

Mr. Weill makes a similar point. Escorting a visitor down his hall of tributes, he lingers at framed charts with multicolored lines tracking Citigroup’s stock price. Two of the lines compare the price in the five years of Mr. Weill’s active management with that of Mr. Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway during the same period. Citigroup went up at six times the pace of Berkshire.

“I think that the results our company had, which is where the great majority of my wealth came from, justified what I got,” Mr. Weill said.

New Technologies

Others among the very rich argue that their wealth helps them develop new technologies that benefit society. Steve Perlman, a Silicon Valley innovator, uses his fortune from breakthrough inventions to help finance his next attempt at a new technology so far out, he says, that even venture capitalists approach with caution. He and his partners, co-founders of WebTV Networks, which developed a way to surf the Web using a television set, sold that still profitable system to Microsoft in 1997 for $503 million.

Mr. Perlman’s share went into the next venture, he says, and the next. One of his goals with his latest enterprise, a private company called Rearden L.L.C., is to develop over several years a technology that will make film animation seem like real-life movies. “There was no one who would invest,” Mr. Perlman said. So he used his own money.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Entrepreneur Leo J. Hindery, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Entrepreneur Leo J. Hindery, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Part of a Greenpeace ad lambasting Senator Edward Kennedy’s opposition to windmills that would effect his view. Source of image of part of ad: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Part of a Greenpeace ad lambasting Senator Edward Kennedy’s opposition to windmills that would effect his view. Source of image of part of ad: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

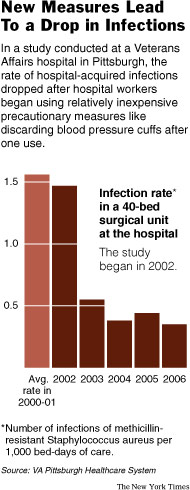

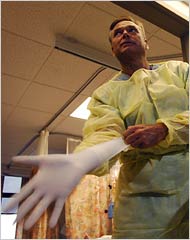

In the photo on the right, Pittsburgh nurse Bill Cunningham, "puts on a gown and gloves before approaching patients with infections." Source of graph, caption, and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

In the photo on the right, Pittsburgh nurse Bill Cunningham, "puts on a gown and gloves before approaching patients with infections." Source of graph, caption, and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.